It's Alive!

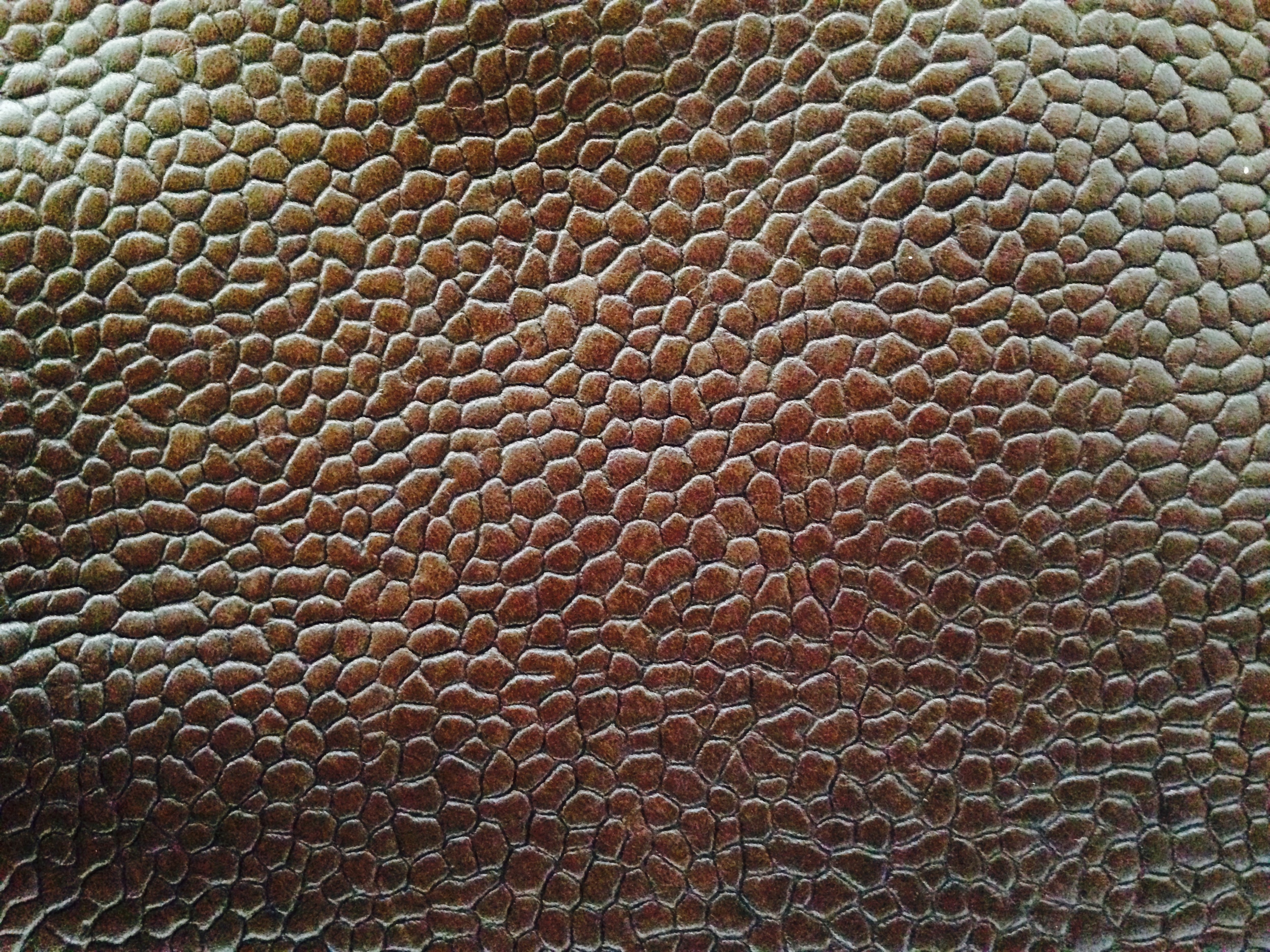

Country calf: pebbly.

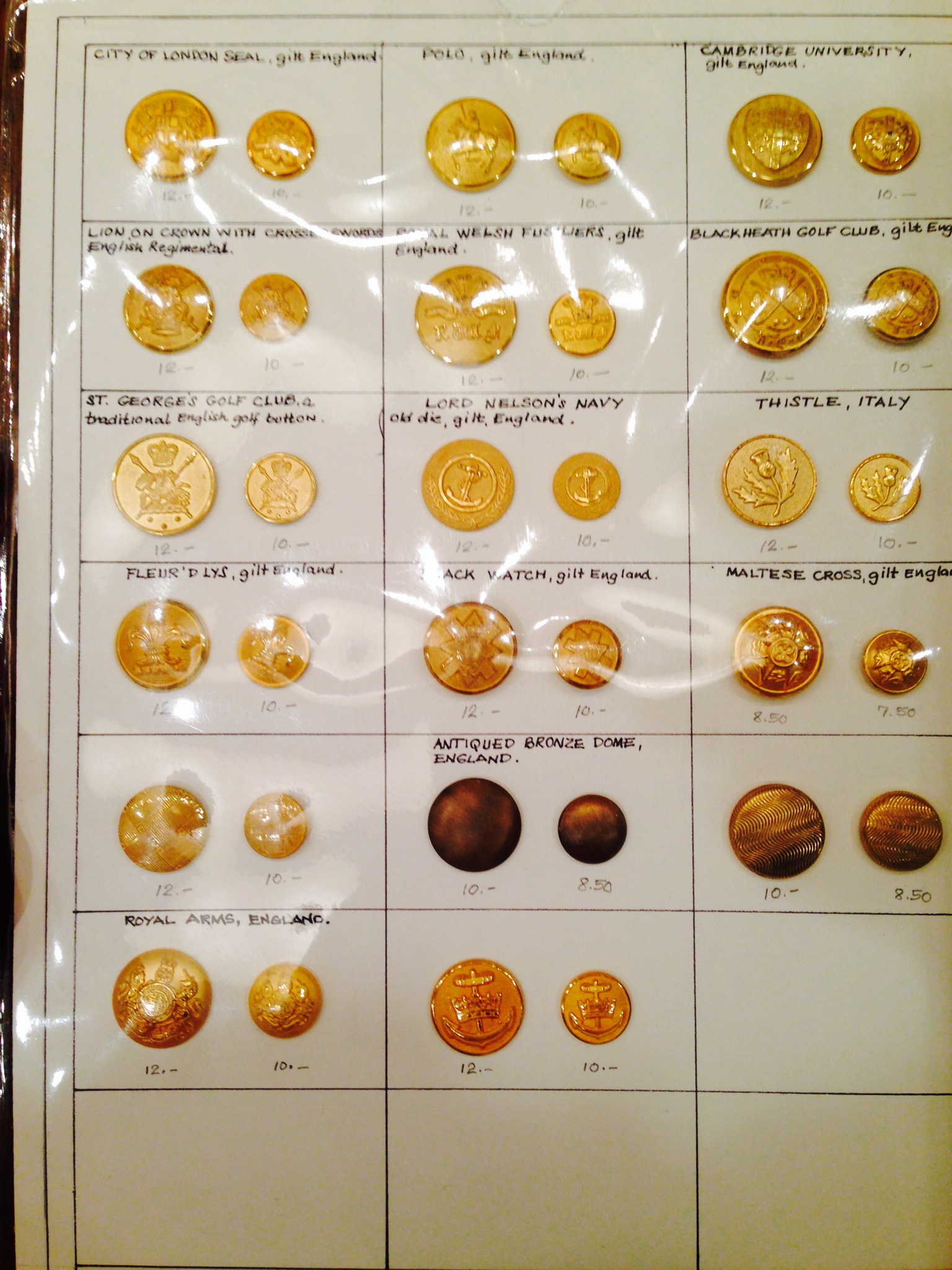

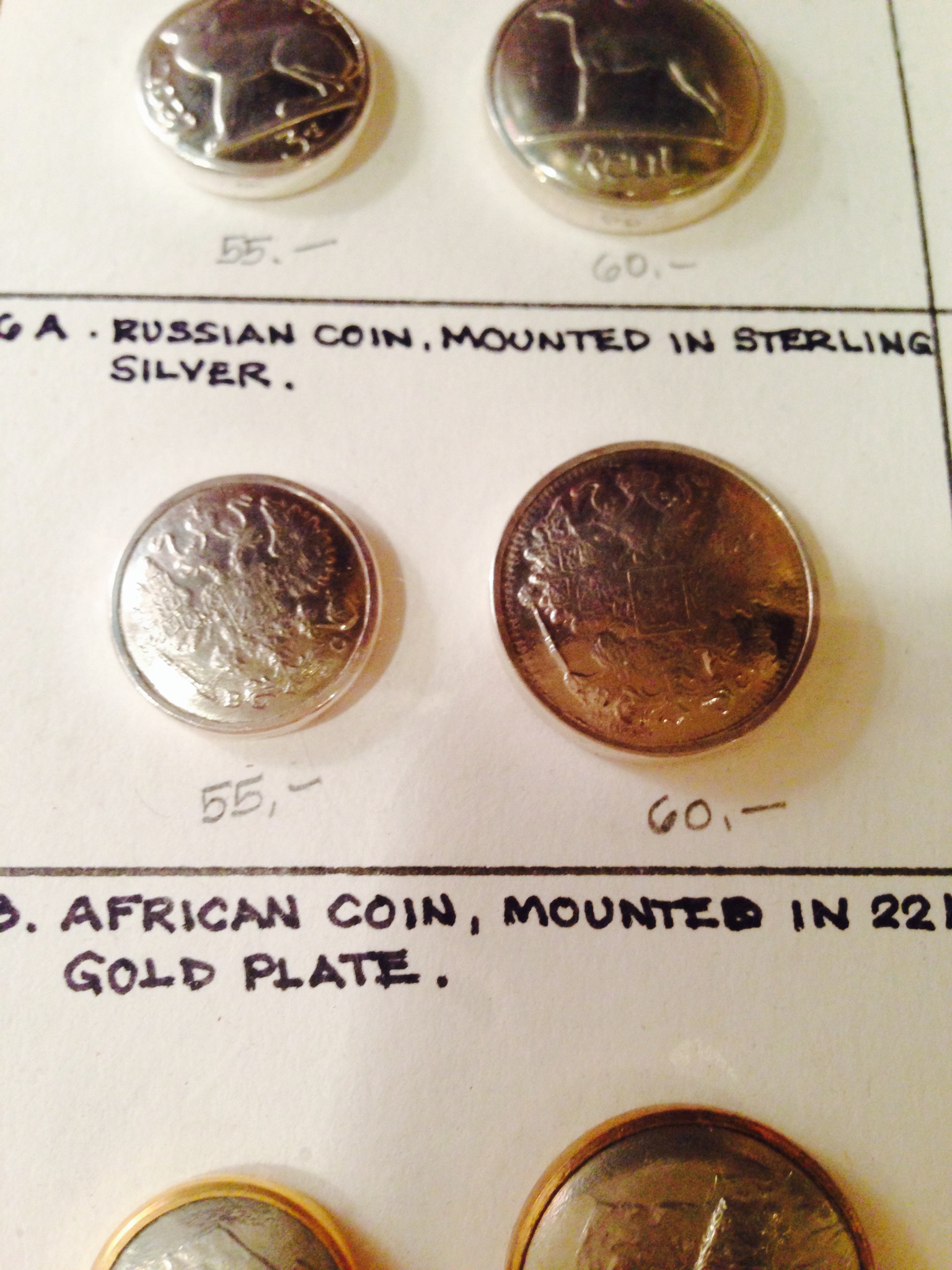

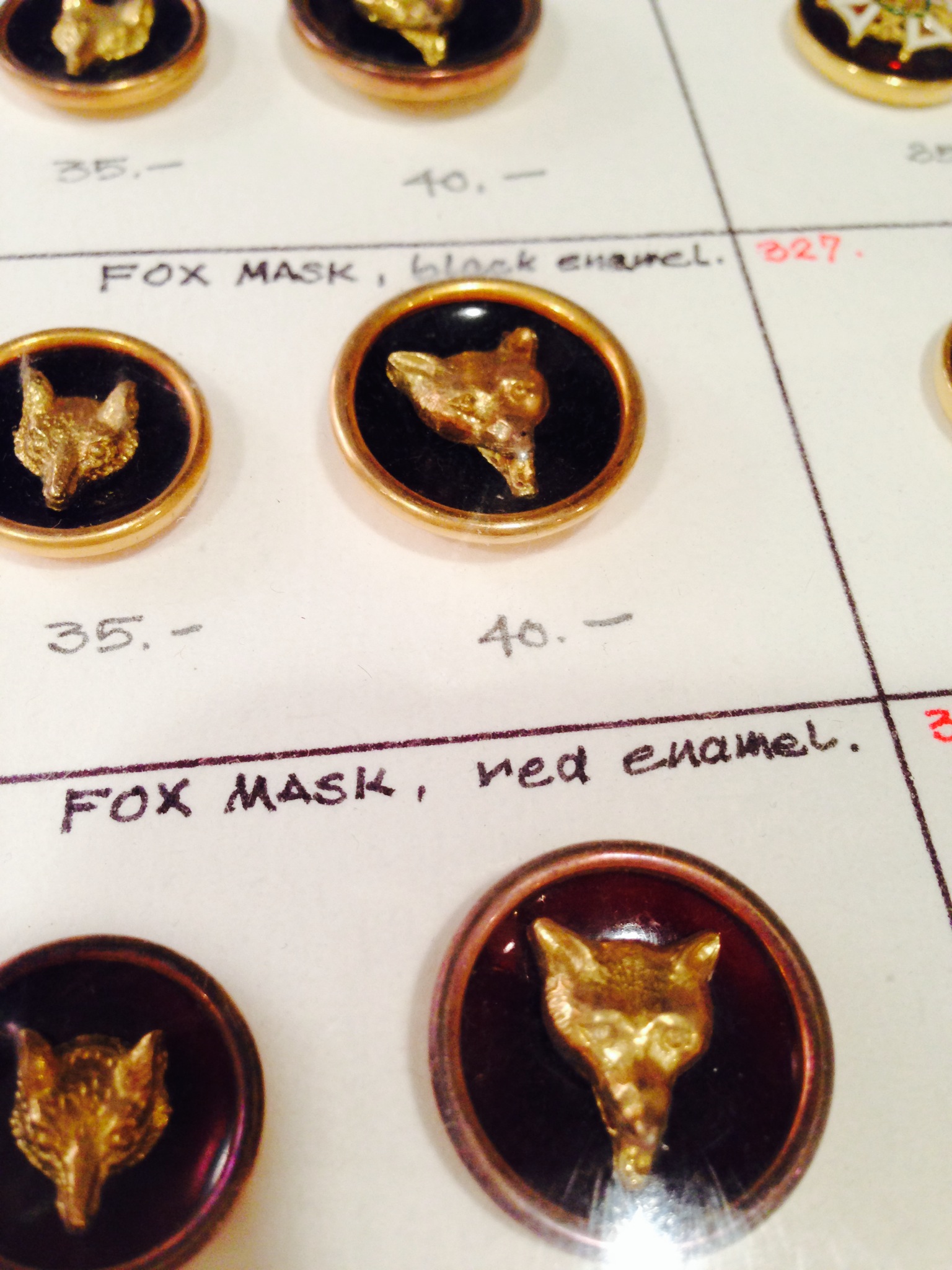

What has three eyes, an excellent tan and an open throat? Possibly the most versatile men’s shoe, of course. By open throat, we are in the world of derbies (bluchers), the more casual configuration of traditional shoe as compared to closed-throat oxfords. However, the reduced number of eyelets, two or three as opposed to the standard five, and lack of any further ornamentation elevate this shoe above the merely casual. The color? Some deep, reddish brown that gets along with indigo denim through pale gray flannel. These were once known as hilo shoes—a sort of truncated chukka boot with a sleek, unadorned shape.

The problem is in fine-tuning the configuration without losing the mind. Do two rather than three eyelets increase the formality or nudge the results from useful to weird? Should the sole be a low-profile single, as seen on oxfords and loafers, or the more rugged double leather typical of derbies? Or perhaps the hilo is an opportunity to use a thin rubber sole for durability and all-weather wear? There is another nagging question. I have long wanted a shoe in the pebbly, characterful leather know as country calf. Is this the right application?

Strangely, when I realize the need for a new pair of shoes, the impulse is as likely to originate as a color than anything else. This is unusual; most men might say something like “I need a conservative oxford for business” or, “suede wingtips would be perfect with my flannel suit.” I suppose I’ve thought something similar, but usually it goes more like this: “tan shoes for summer would be great!” I then realize I would rarely need a tan oxford, which leaves derbies, monk-straps and loafers. Perhaps I have seen a good looking monk-strap recently; inspired, I picture the monk-strap in the shade of tan I have in mind. If no capillaries have burst, I file the idea away for a month or two. Following this gestational period, and if it seems my mind’s eye was firing on all pistons when conceived, the project gets green-lighted.

A monk's defining feature--the buckle. A more sensible option to the rather obscure hilo?

Speaking of monk-strap shoes, they seem to occupy a similar place in a man’s shoe wardrobe to the hilo—neither particularly dressy nor so casual as to never see wear with a suit. In fact, I vacillate between this hilo idea and a sturdy monk even now as I try to bring the vision into greater focus. Versatility seems such a straightforward concept; the more one meddles with its underpinnings, though, the more likely it becomes to lose control of the reins, the project itself generating its own, rather disconcerting life.

Certainly no one shoe can do it all, from dinner jacket to jeans. But I bet a pebbly, reddish, three-eyelet derby would get a lot of use in-between. Of course there is always the risk of creating something ghastly—something that ticks all the requirements and sounds sensible, but, once released from its box, causes the sharp intake of air from its creator. I think only the most experienced men nail the details every time ; I feel a more realistic aspiration is in learning to avoid the monstrous.