Heavy Metal

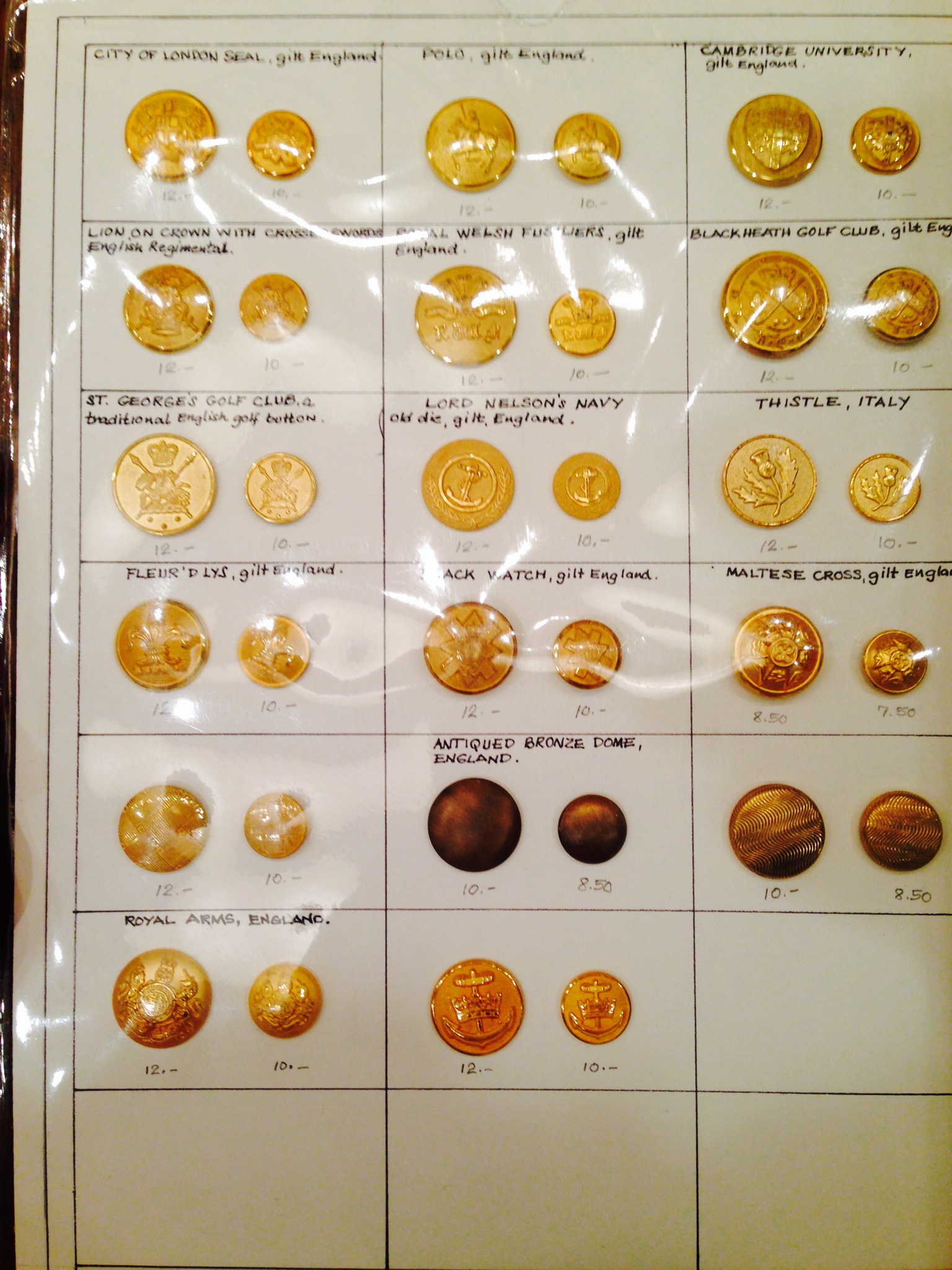

The blazer wall (part of it, actually) at Tender Buttons.

Where did I come into the idea that, with perseverance and an easy attitude, a suitable blazer button would make itself known through the piles of uninspired, unentitled, ugly, and unworthy? Why should I ever have thought something handsome and understated would have found me? I suppose some naiveté can be forgiven; the internet promises vast choice, but remarkably few viable leads. And even trace impatience erodes the delicacy of the task. Choosing a blazer button demands respect for what’s at stake: the finished garment’s character.

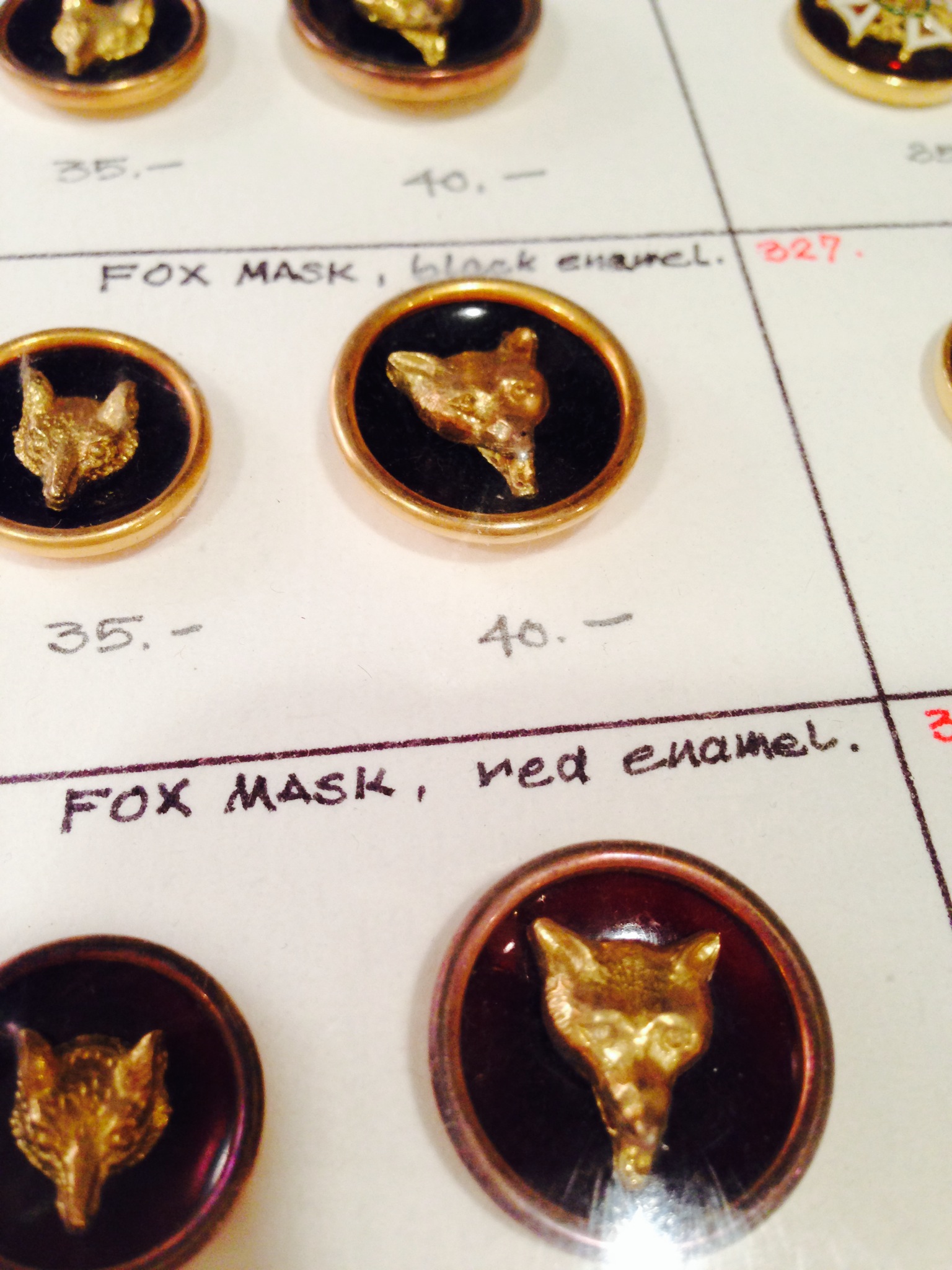

The smart shopper will know in advance what the things on buttons mean. At the top and most explicit level, school, club and military emblems. These are easy to eliminate from a search if one has no attachment to the institution. Paradoxically, these are the most prevalent. They tend to be intricate, colorful and loaded with busy symbolism. My impression is they are more secret handshake than understated elegance anyway. Generic symbolism comes next. These cast a broad net: lions (monarchy), thistles (Scotland), anchors (nautical), but always strike me as adrift in vagueness. Does the thistle-wearer endorse an independent Scotland? Will the anchor-wearer blush if asked about his boat? A subspecies of this category is the literal symbol: golf clubs, racquets, guns, foxes, pheasants, ducks etc. These are safe for the sportsman who wields or shoots at one of these, but, again, what if the wearer just likes water fowl? The rarest category is the blazer button free of anything literal or symbolic—the metal disk with some subtle machining or nothing at all. This is what I’m after.

Keep in mind though that no garment is ever entirely free of association. A tank-top means something; so do horn-rimmed spectacles. A navy blazer with metal buttons, regardless of what appears on them, will register some association with those who encounter it. My intention is that my blazer registers as a blazer rather than an orphaned suit coat; I am relying upon metal buttons to some extent, but also upon the textured hopsack cloth and gently swelled edges. Put another way, the buttons are only part of the display.

New York City’s Tender Buttons was the most promising brick-and-mortar source. While a charming place, the choices are either very specific (Civil War uniform buttons set in 18K gold) or, and it pains me to say this as the place really is lovely, rather generic. Online (or through a tailor) new buttons can be had from two premium English sources: Holland & Sherry and Benson & Clegg. The former offers an edited selection of generic and literal symbols alongside a handful of plains all in solid brass, some enameled or plated in precious metals. The latter offers much the same at a lower price point as well as school, club and sporting buttons.

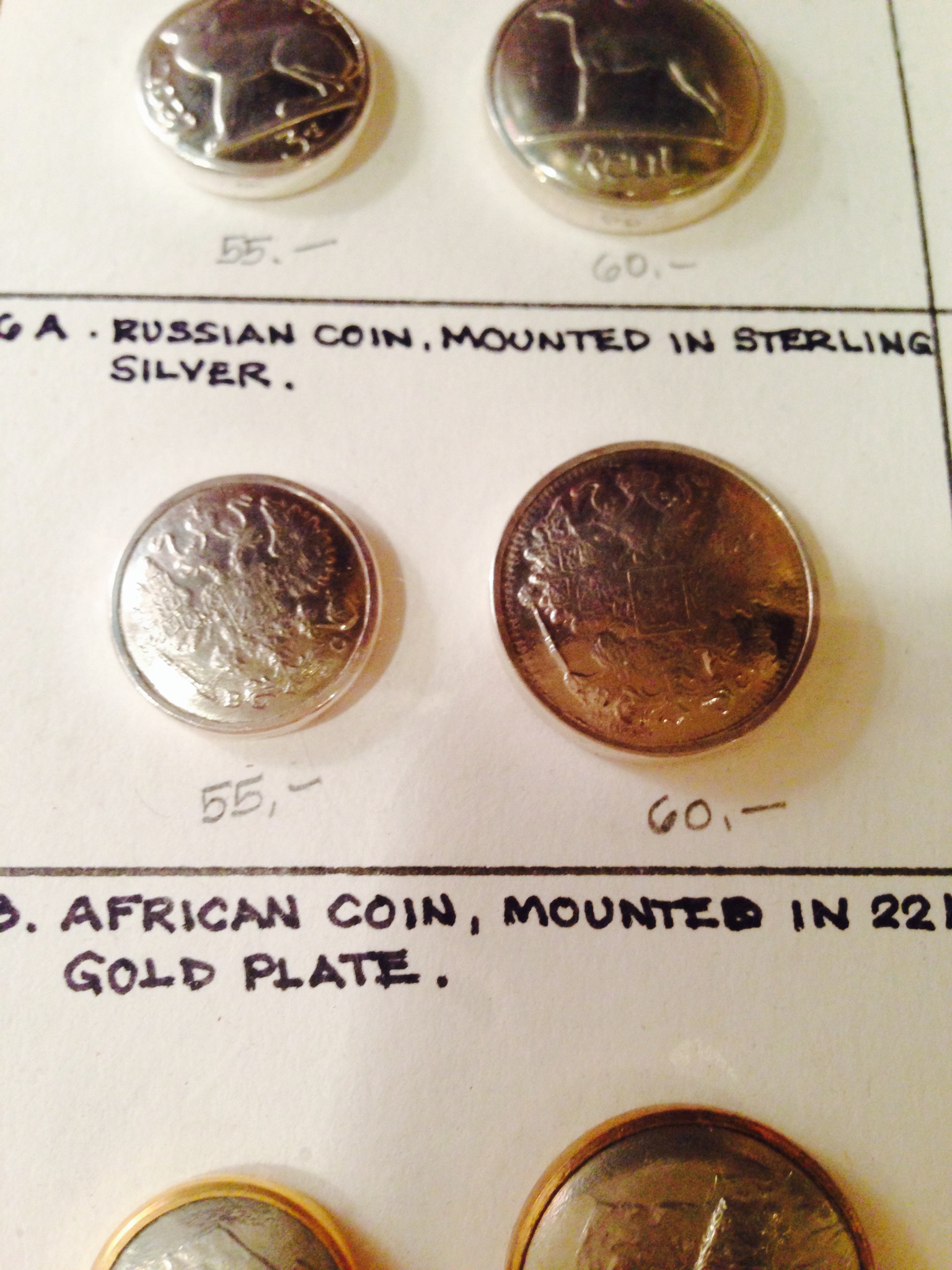

The wild card in this endeavor is the wider marketplace—the public auction or street vendor. Perhaps one has Welsh or Swiss roots, or was born in Hong Kong or Auckland. Perhaps one’s uncle was a paratrooper, a crack shot or a wizard. Maybe the albatross or loon is a point of personal fascination. Buttons featuring all of these exist waiting to be snatched from the ether. A family friend recently sent me an image of some buttons she found at a market with hopes of deciphering the strange symbol of a chimeric creature wrapped about a gothic column. I haven’t turned up anything yet; if she wears them perhaps someone will one day approach with an elaborate handshake. Now that would be a good button story.