A Scrooge Gets Dressed

Red and green toned down.

It’s tempting to pose the question baldly: why do otherwise conservatively dressed people slip into costume around the holidays? But doing so gives the impression of a fusty wraith, passing silent judgement from the shadows of a canapé display. I’m not that ghost of Christmas present; I don’t so much mind the silly sweaters and un-entitled tartan. Red socks have never once given me indigestion. Of course, like everything else, I often wonder if most efforts wouldn’t benefit from a few sensible parameters.

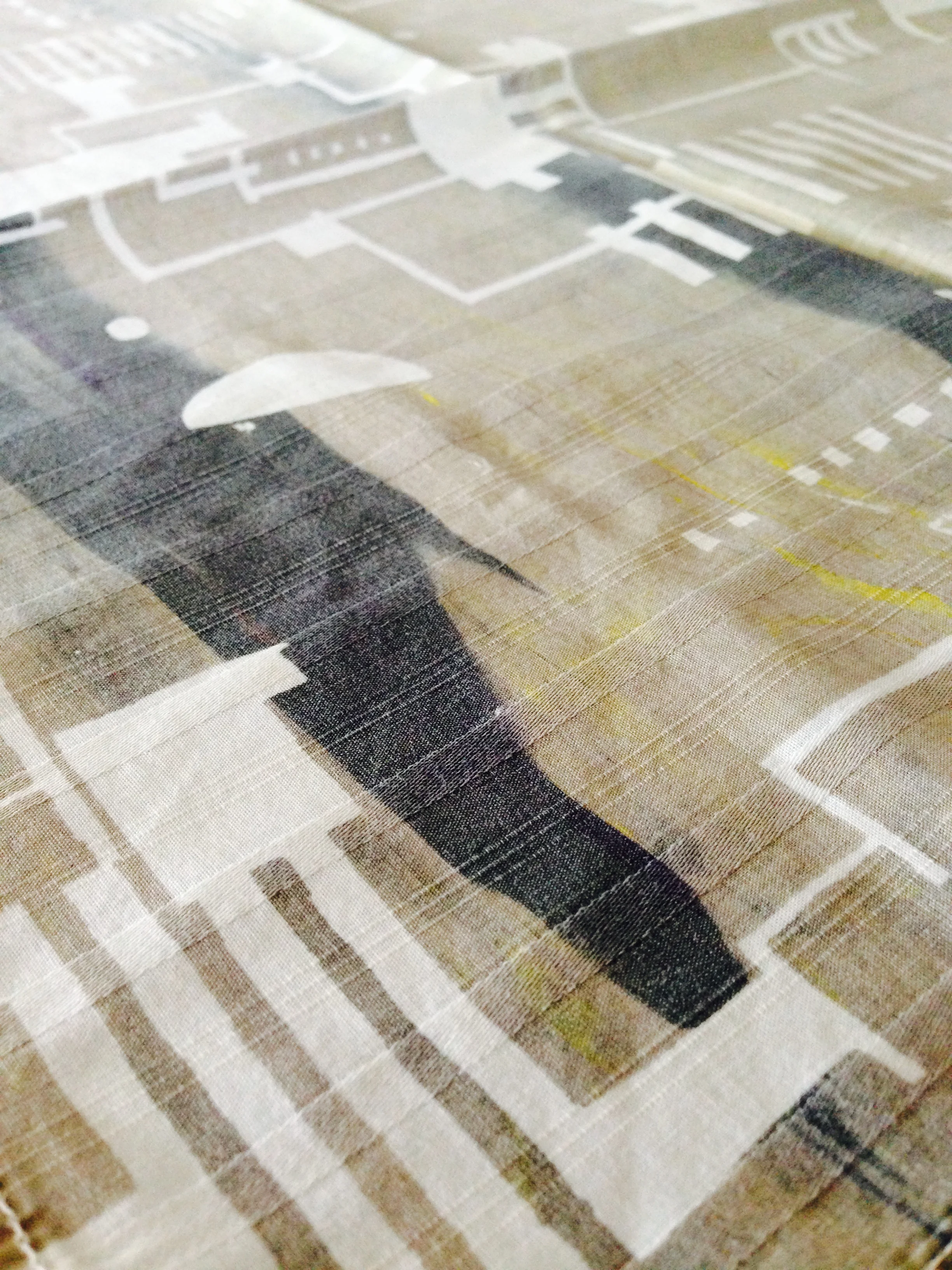

I recently heard an interview with horror film director Wes Craven in which he discussed the creation of Freddy Kreuger, who wears a red and green striped sweater. Apparently he chose the two colors after himself hearing a neurologist describe the combination as the most jarring and discordant for the human brain to process. I’m happy to finally learn I’m not alone. Primary red and secondary green are oil and water, and when mixed, protest loudly. Strangely, the instant an additional color is introduced things improve, and all is well once either (or preferably both) are darkened to, say, burgundy and olive. In fact, dark red and green, along with vibrant navy, yellow, white and black are the principle shades used in the most familiar tartans, and who would argue with that sort of lineage?

Speaking of tartan, it’s best in small doses. We’ve all passed holiday store windows that groan beneath heaps of contrasting tartan, the mannequins within either too sozzled on claret punch or too consumed in their own layers of velvet and plaid to notice. The truth is, outside of those rose-tinted displays and exposed to the harsh winter light, tartan reveals itself for what it is: distinctive cloth designed for ceremony. That’s not to say a well-deployed waistcoat or wool tie isn’t in good taste; it can be, as long as the wearer is: a. aware of what it is he is wearing and b. not inclined to its overindulgence. A true Scotsman, entitled to a tartan, might wonder what marketing distortion has lead to his becoming associated with the American holiday season, but I will leave that up to the unhappy wearer who encounters said fellow (and his dirk).

All bets are off when relaxing at home.

Finally, figures. I suppose the fair isle sweater, a personal favorite, is to blame. So intricate are the traditional patterns of these colorful knits that one could be forgiven for mistaking some fragment for a jaunty snowflake. But doing so opens the floodgates to the literal figure and it doesn’t take long before reindeers and St. Nick, all rubicund and knowing, begin appearing on ties and scarves Thanksgiving through Boxing Day. Like Jeeves, Bertie Wooster’s sensible valet, I draw my personal line at literal figures. And not just outside of the holiday season; pheasants, grouse, venison and bunnies all look better well-roasted on a platter than they do on accessories. Bah, as the saying goes, humbug.

What, the merry reader might ask, am I afraid of? I will call it the Victorian Effect, named after a recent outing for afternoon tea in a well meaning hotel that, in an effort to enhance holiday cheer, hired a group of carolers. They were excellent, with one small exception: all five of them wore period costumes of pleated velvet capes, brocade waistcoats and stovepipe hats. I might be alone in thinking it, but Christmas is somehow cheapened when we indulge cliches as a way of wringing out every half ounce of cheer. I think the same applies to how we dress for the social events of the season. Anyway, what’s the matter with moderation?