Reasonably Seasonal

This Cote de Brouilly could go either way--chilled or cellar temperature.

Perhaps four years ago at a lively bistro on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, I sat for lunch with my wife on a particularly hot day. She was rather pregnant at the time, and perhaps because of this, we were given a table very quickly, despite what appeared to be an impatient lunchtime crush of regulars. The tables were tightly arranged in the small dining room and so eavesdropping was unavoidable. Next to us sat two men; while I hesitate to say they were rude, their manner was certainly brusque, and more so than might be excused by local custom. The waiter, a Frenchman, was patient while one of them studied the wine list, finally jabbing an index finger at a name. The exchange was brief but perfect:

“Is that the red wine you are supposed to drink cold?”

“That Beaujolais would be fine chilled.”

I was impressed how expertly this professional dealt with what, for lesser waiters, might have been an opportunity for haughtiness. His response was delivered with a gracious smile, but the message was clear: you may drink that particular Beaujolais chilled because the day is hot and the spirit in here conducive. As a devoted Beaujolais drinker, I was satisfied. This young, uncomplicated French wine can, indeed, be chilled. Some combination of varietal (Gamay) and fermentation method (carbonic maceration) produces light bodied, fruit-forward and yeasty wines without the tannic astringency that would become metallic and flat once cold. The problem is that the fashion for chilled Beaujolais tends to creep outside of those appropriate moments. Ordinary Beaujolais doesn’t need a chill to be good, and the Crus (small, pricier producers) can demonstrate complexity and nuance that would be a shame to flatten out with chill.

When it works, though, few wine experiences seem as clever. So ingrained is it that red wine should be served at room temperature, that any sign of chill seems an error. Perhaps this is why red wine is often served too warm; the fear of faux pas creates an overcorrection. Counterintuitively, Beaujolais almost becomes more serious when chilled. The signature fruity nose develops juicier and darker notes and a bracing structure can emerge where before there was little. Well-chilled Beaujolais is also dangerously drinkable, and not unlike rosé, is a practice best reserved for those warm weather daytime events where a few drinks seem less an indulgence than a right. The waiter was spot-on; chilled Beaujolais is more about atmosphere than correctness—the enhancement of time and place through an unusual practice.

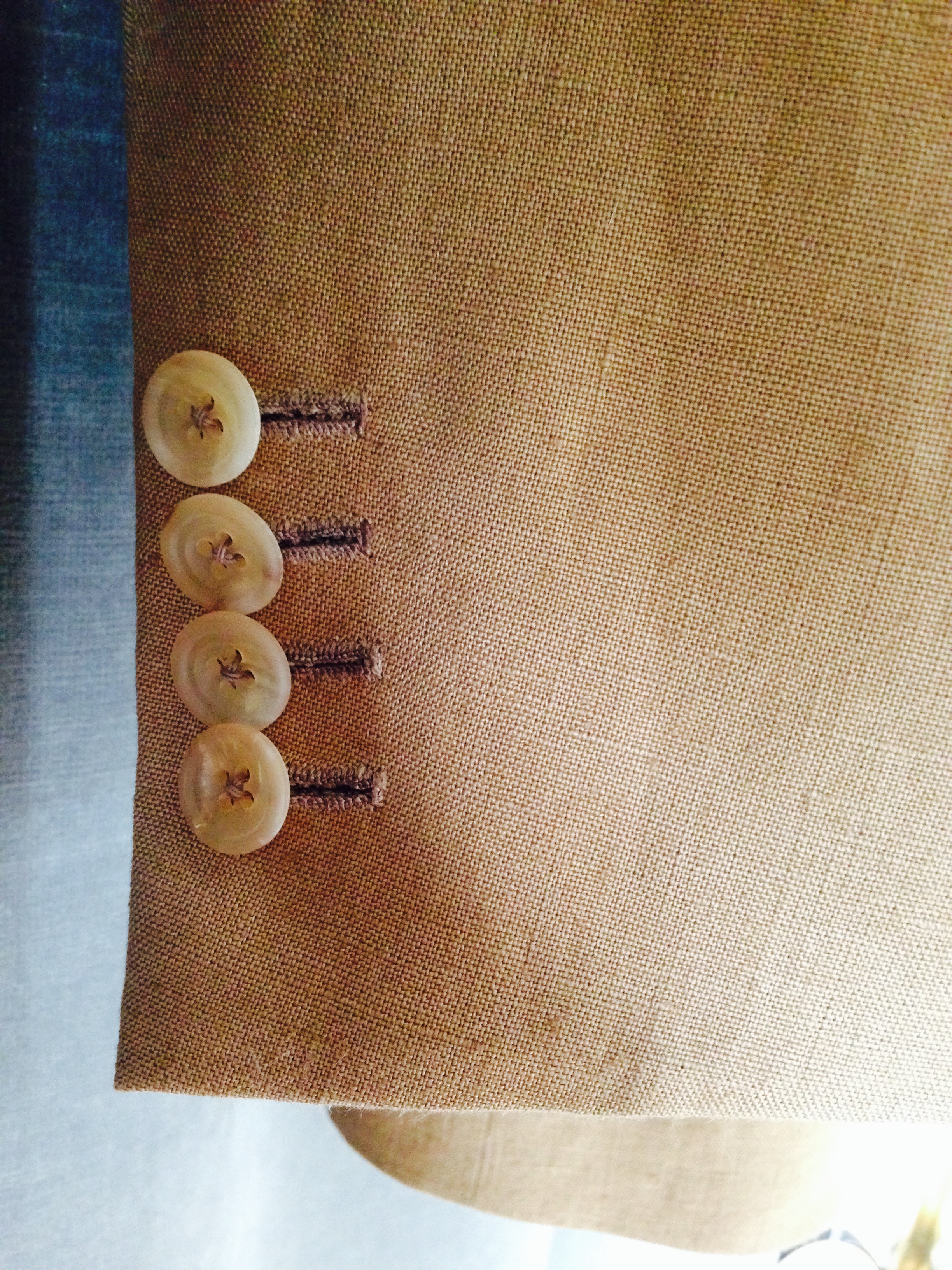

A surprisingly similar sensation can be had by going sockless. A collection of quality, over-the-calf hose can be the difference between dressing and dressing well. Having multiples of sober colors is an efficiency, and a complement of less serious patterns is the mark of a more sophisticated dresser. But even the most comprehensive collection can’t compete with the thrill of going without on those warm and casual occasions when even the sheerest, coolest wearing versions stifle. I adore my own collection of lisle, merino, silk and cashmere, but my favorite day on the sock-wearing calendar is the one when the breeze finds its way between loafer and trouser cuff.

But socklessness, like chilled red wine, can creep too. Any occasion more serious than a non-business lunch or casual outdoor event really requires socks. I don’t usually look out for ankles, but a bare one at a wedding or business function is hard to ignore. It’s funny to think of a man’s ankles as being distracting considering our collective tolerance of exposed flesh these days, but somehow that little patch of skin between foot and calf is weighted differently than midriff and décolletage. Specifically, it signifies leisure. This is why a tie requires socks; on younger men forgoing the latter looks affected, on older men, like a jarring omission.

The only real danger in chilled Beaujolais or socklessness is deploying either too regularly. This is often the case with seasonal indulgences; they only delight when experienced in contrast to the expected. Of course this cuts the other way too; the instant the practice feels routine, a return to more conventional habits is welcome. We are blessedly early in the season though, so at least once a week I will be the guy drinking cold Beaujolais, ankles very much in the open.