For Keeps

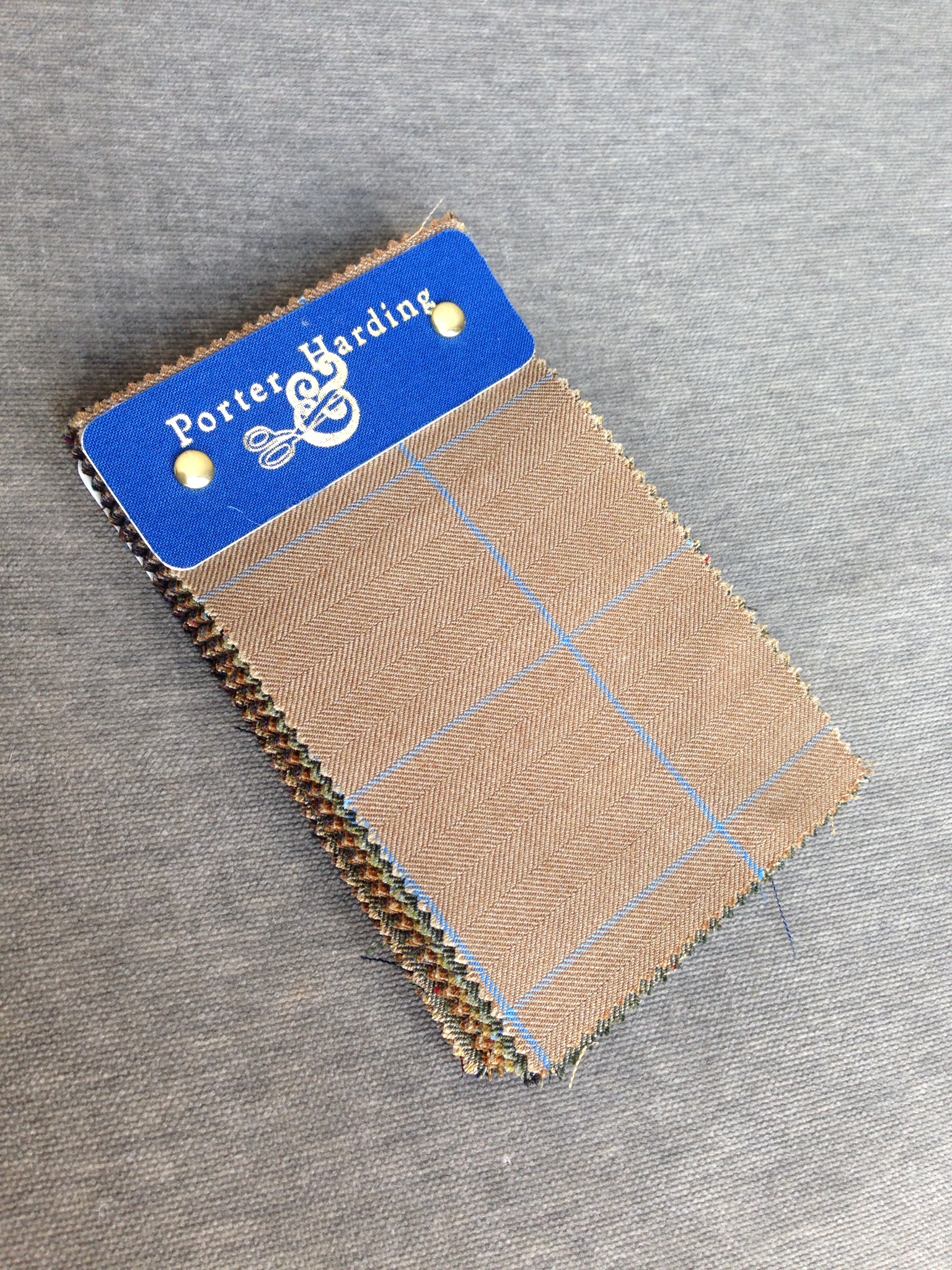

I am not sure I could put a hard percentage to it, but there is little doubt: much of my interest in men’s clothing originates in the names. Some are obvious portmanteaus; thornproof achieves what it claims because, as tweeds go, it is exceptionally densely woven. There’s the vaguely French: covert cloth, where the “t” is silent, began life as riding and hunting cloth, but, with its marled two-tone effect, proved too handsome not to be fashioned into polished topcoats. What about cavalry twill, which suggest mounted charges and smoke-filled officer’s quarters, or whipcord, which sounds as durable as it proves to be. In among these I have long admired a cloth with a more complex suggestion: keeper’s tweed.

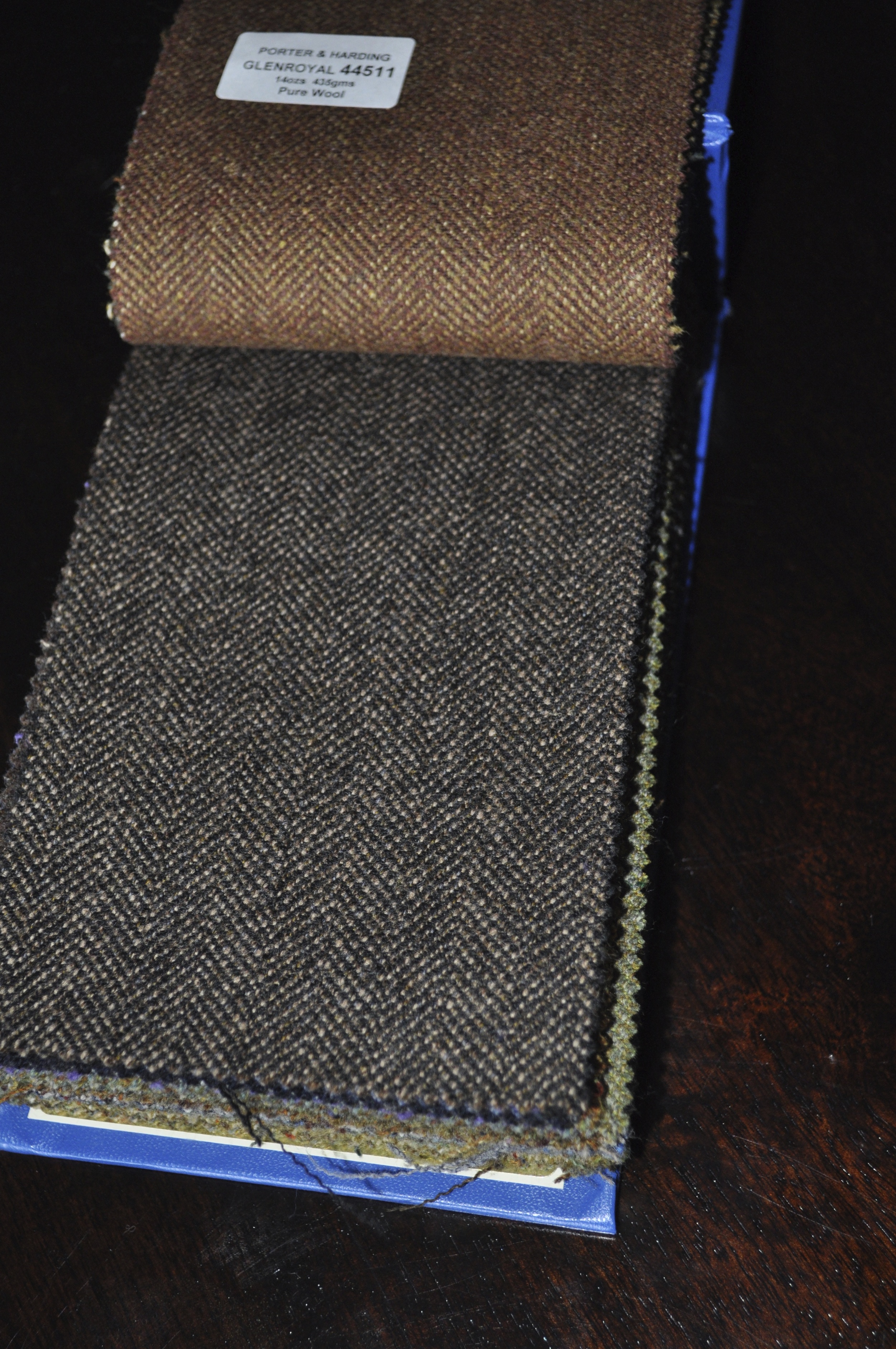

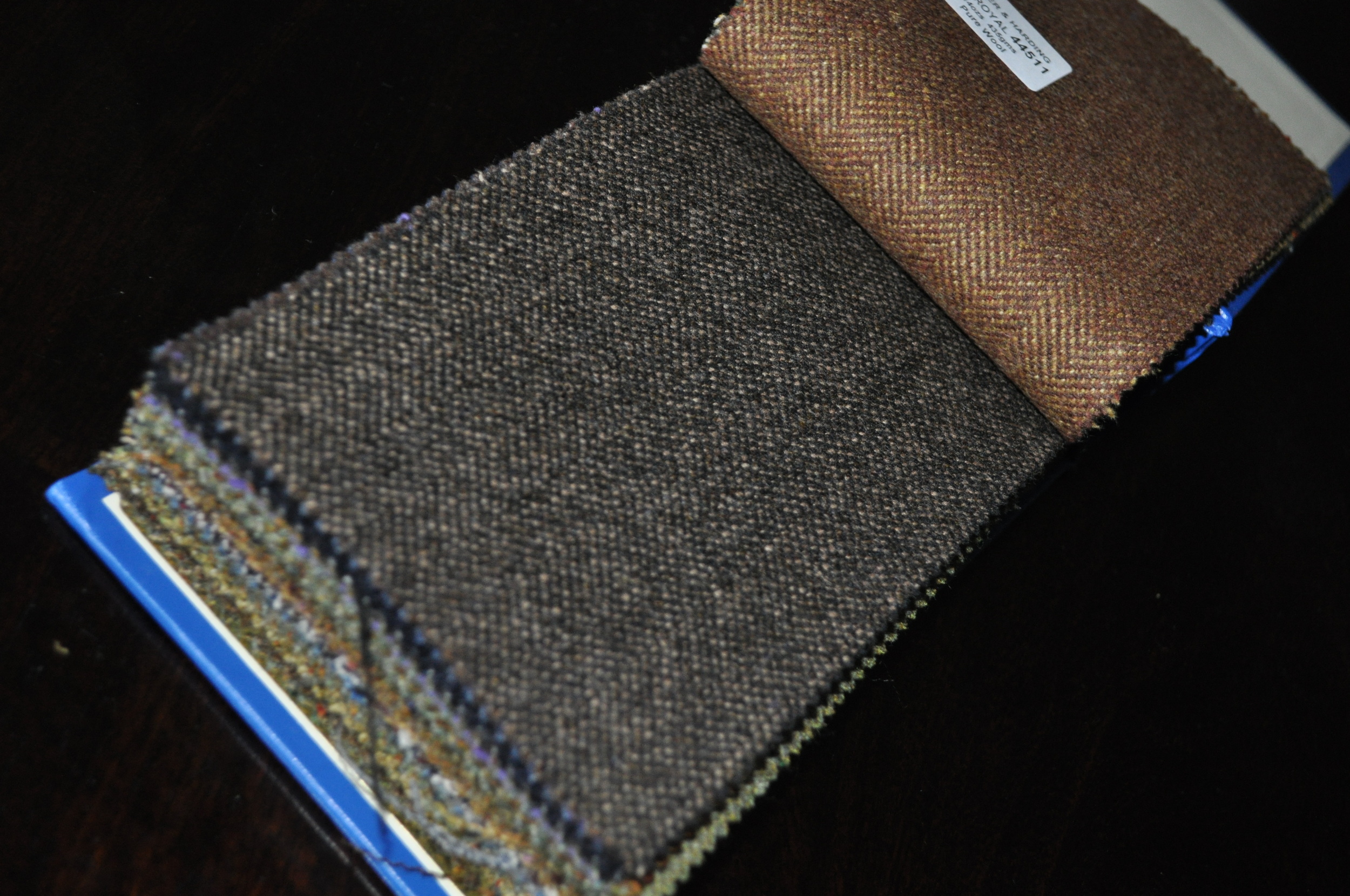

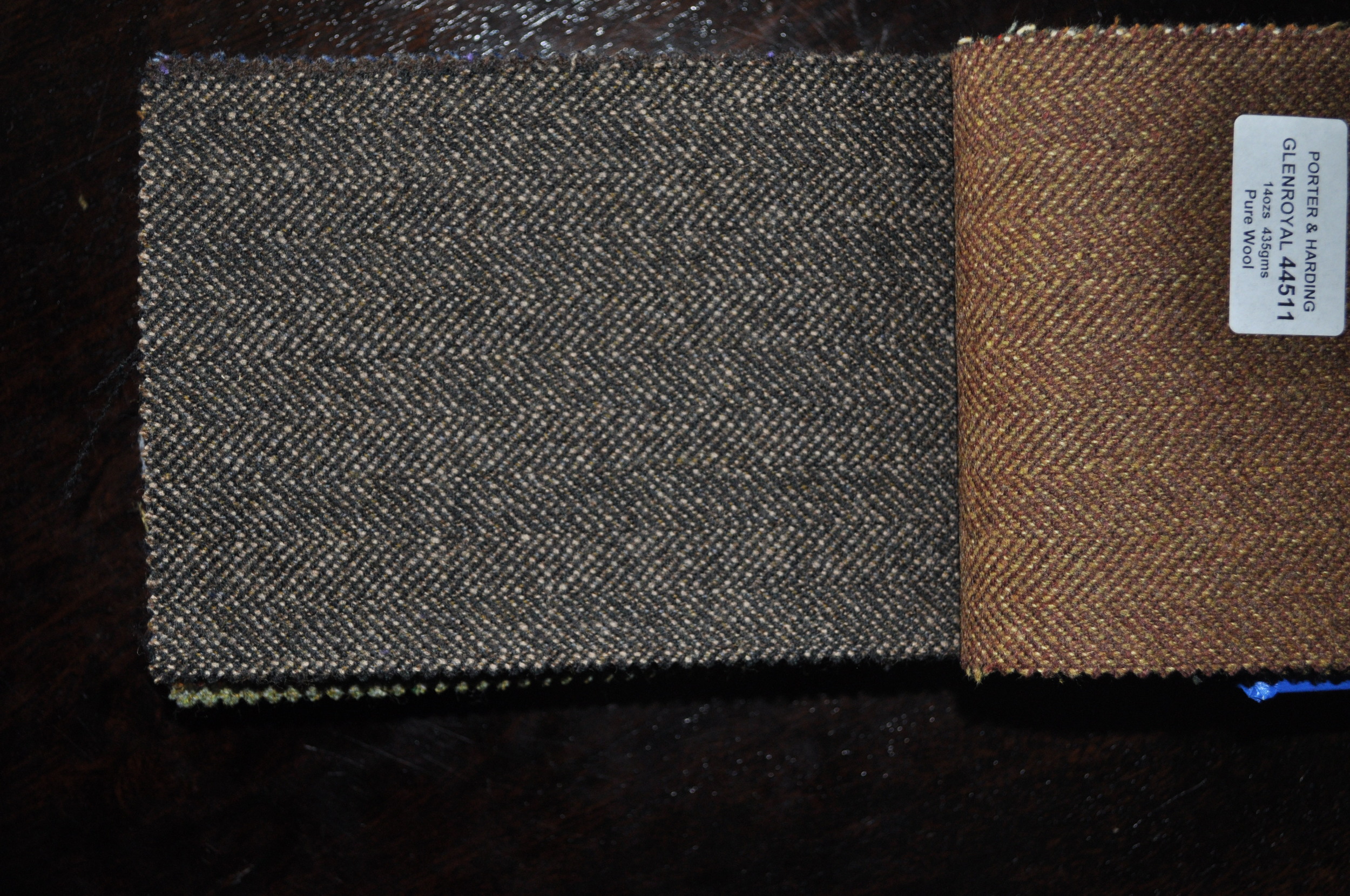

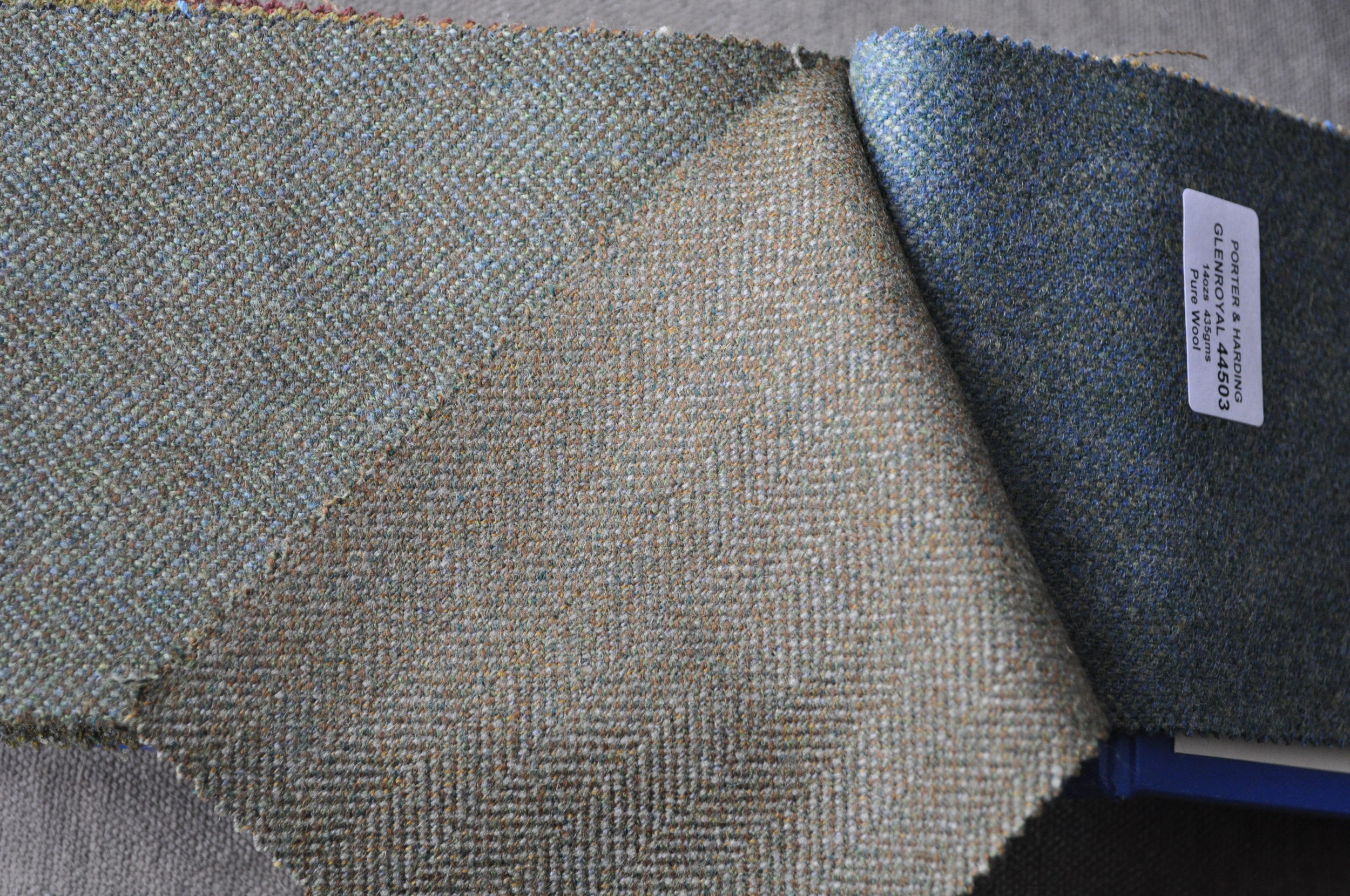

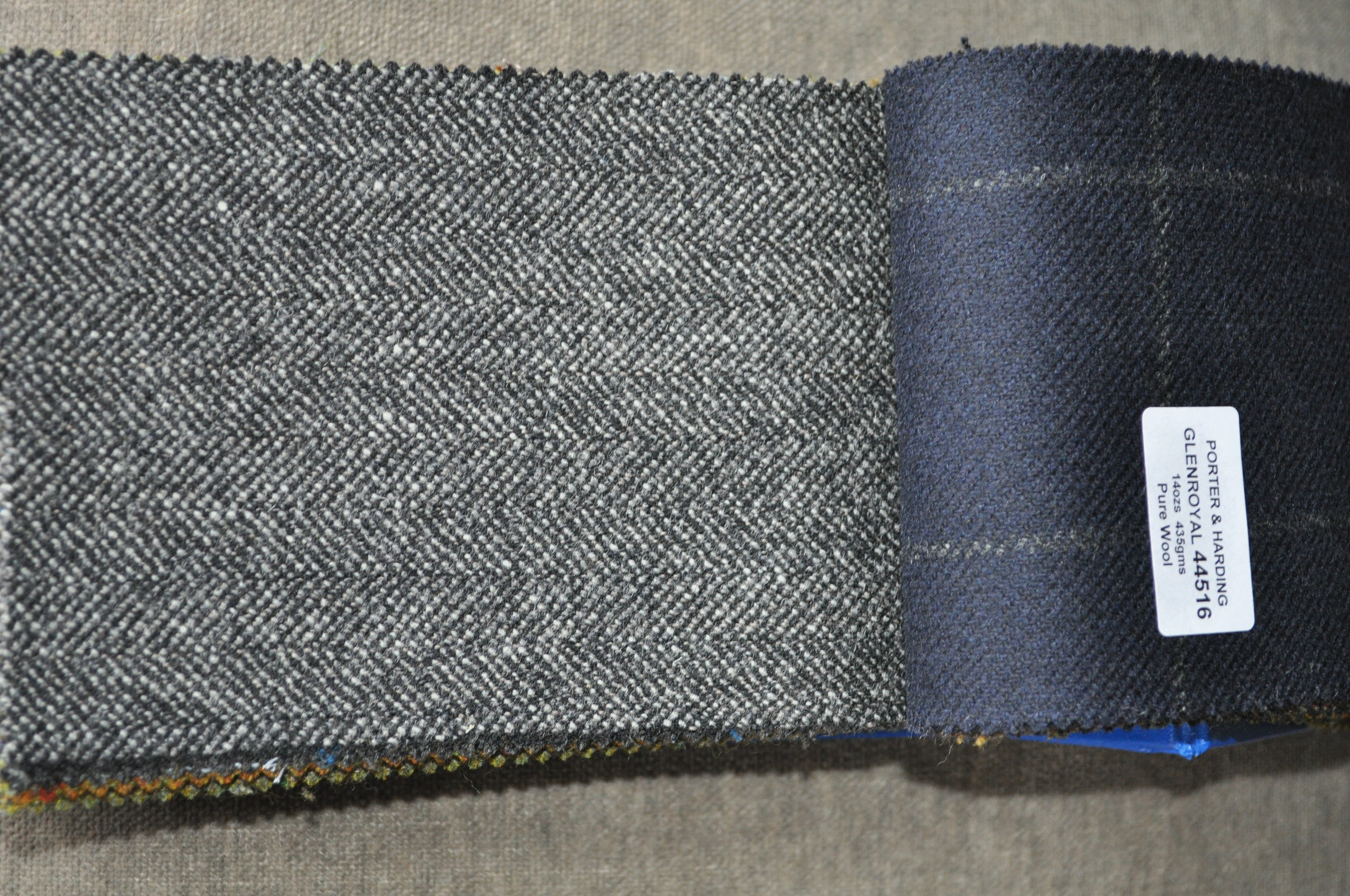

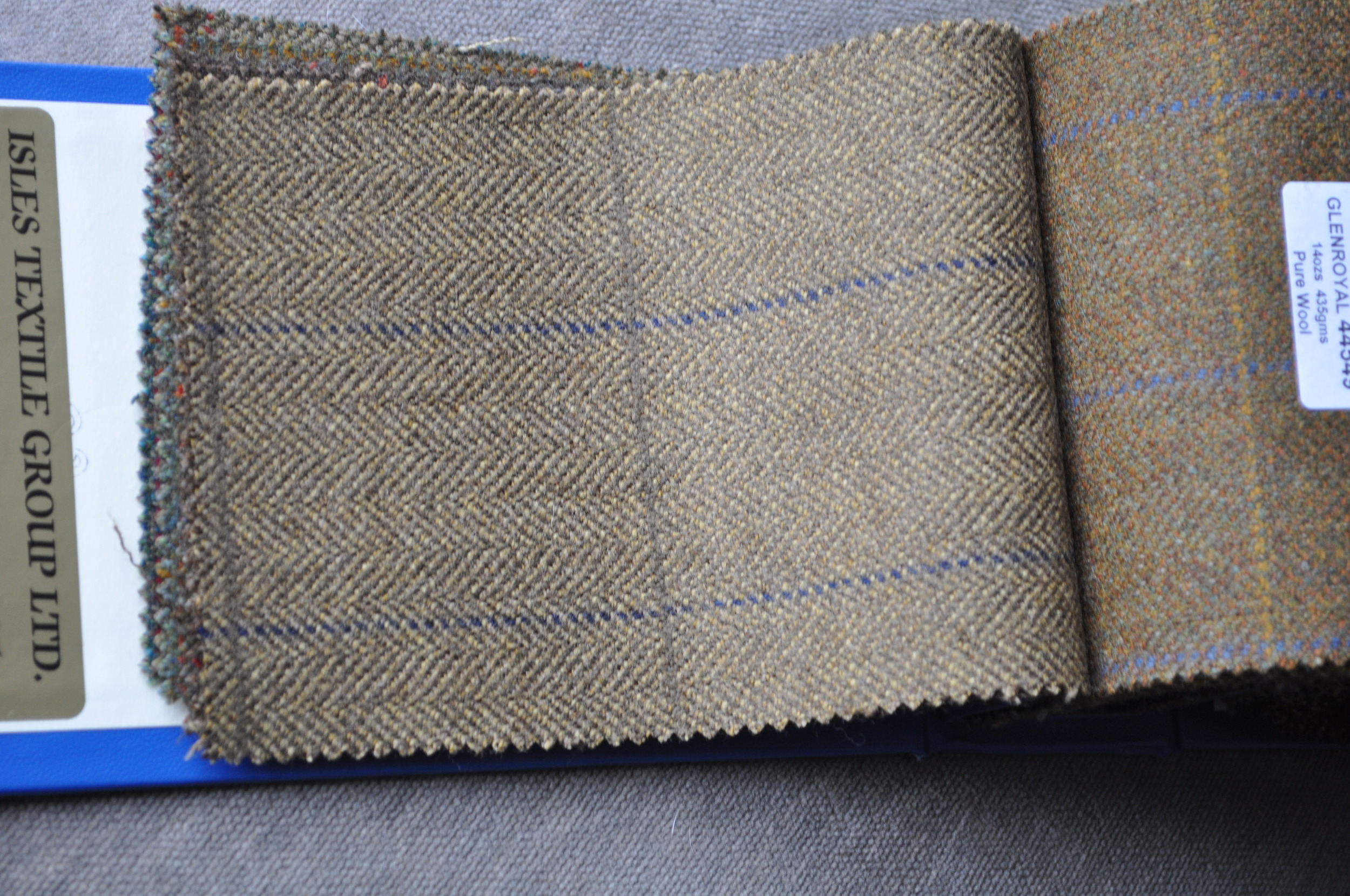

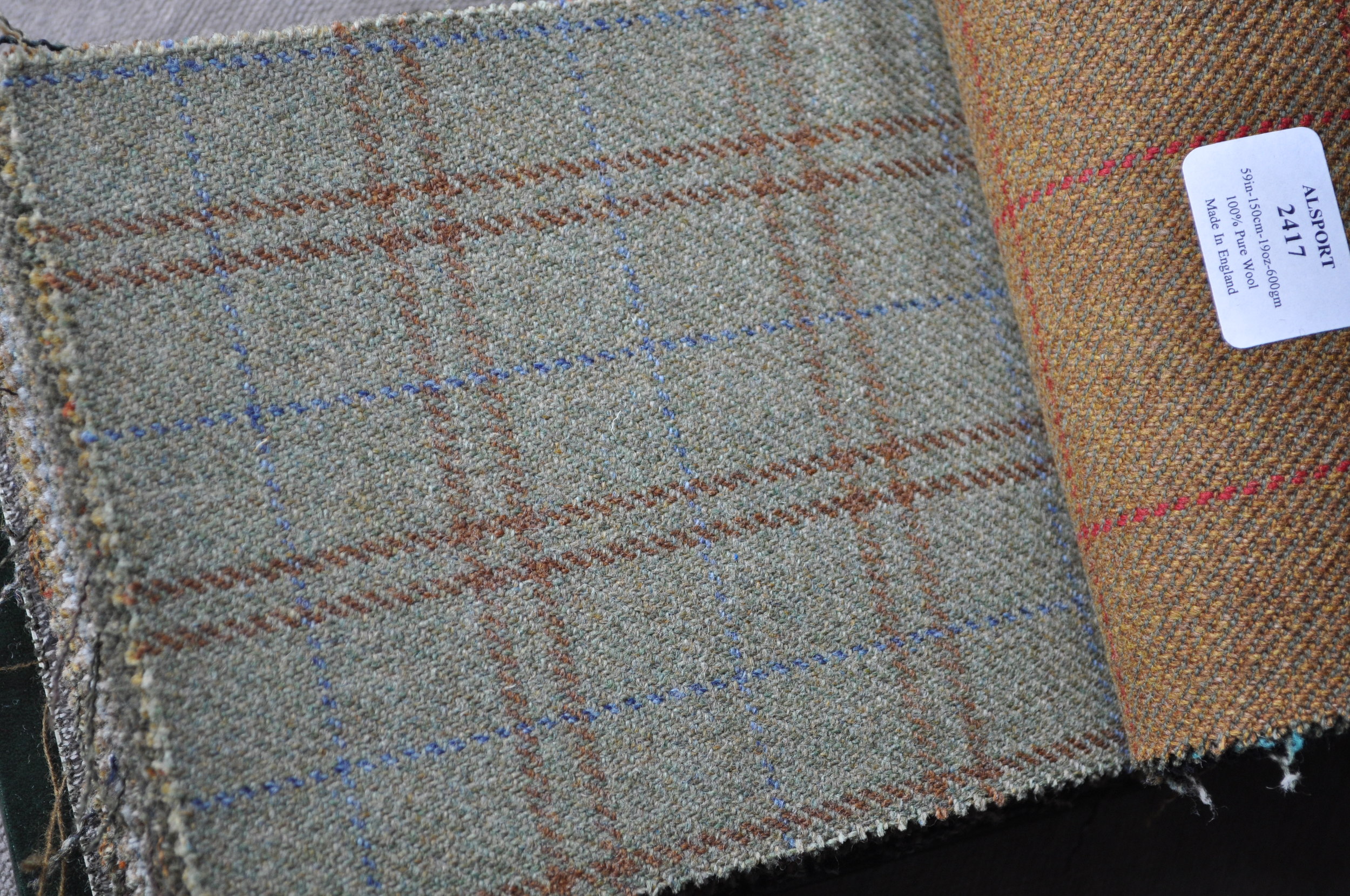

This is the original working tweed—the heavy and muted cloth reserved for a country estate’s gamekeeper and his staff. There is no regulated weight range, although I would argue anything under seventeen ounces a yard, while durable and heavier than much of the ready-to-wear market, is just tweed. Twenty ounces is a good starting point; twenty-four, better. But weight alone does not make a keeper’s tweed. The patterns tend to be far less elaborate as well, and the colors, while remarkably rich up close, resolve almost universally to either lovat, dark green or olive. The lack of exuberance of a classic keeper’s tweed is a matter of camouflage. But is blending into the fields and fens just as important as standing out from the shooting party itself? Put another way, lilac overchecks and royal blue plaids might look dashing on the backs of those wielding the guns, but the serious business of managing land has only ever called for subtly and performance.

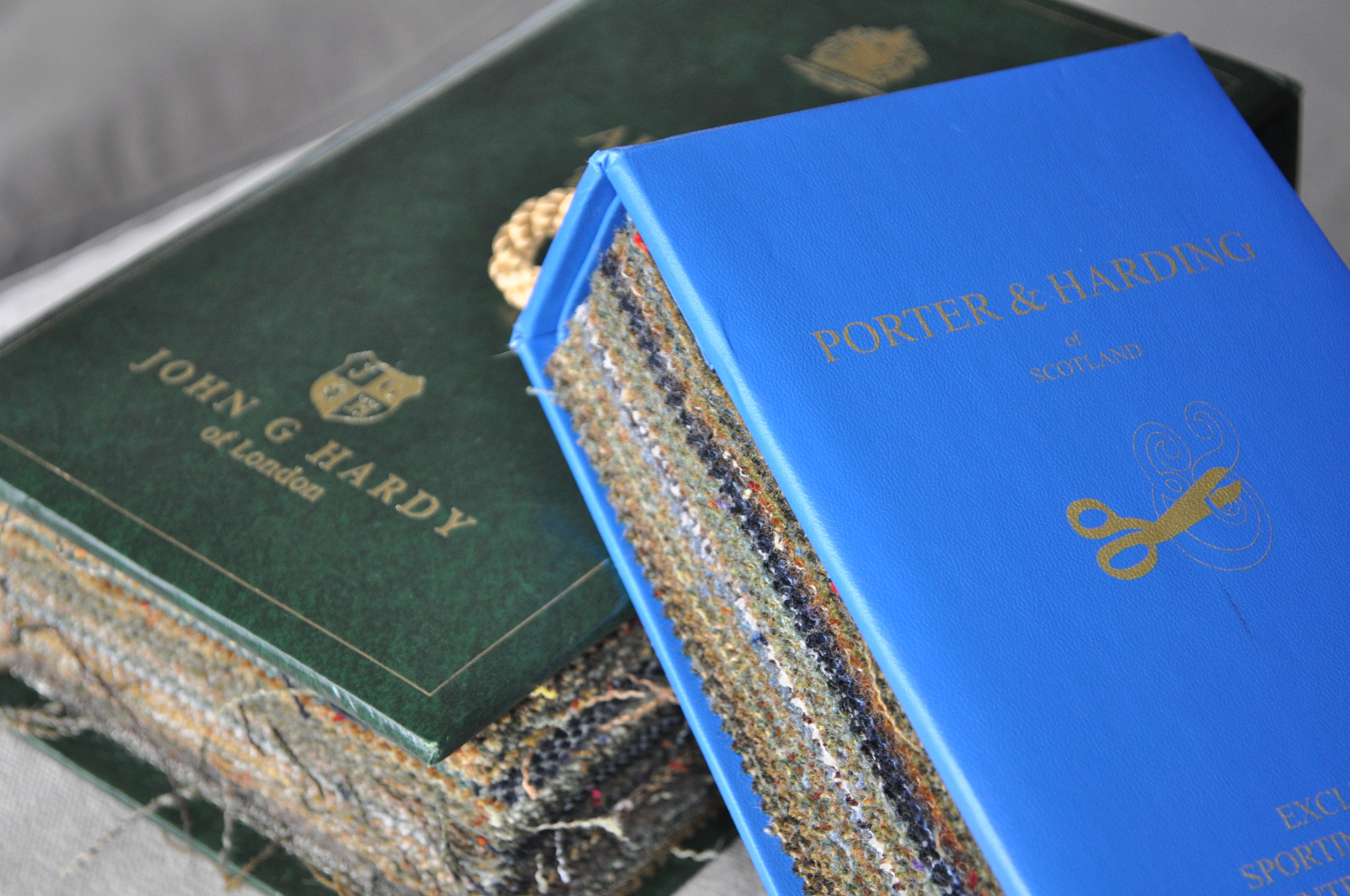

Of course few today seriously require either. But the spirit of this historical cloth remains in books like W. Bill’s Keeper’s Collection. I do not have a driven hunt in my future (as either a beater or a shooter). I do, however, have dogs to walk and outdoor sports events to attend. I also have a beloved pea coat that, after fifteen years of hard wear, has packed it in. I suspect that with a few tweaks in design—perhaps a throat latch, slightly longer skirt and an action back—a sports jacket made of keeper’s tweed would be a sensible replacement. This is a critical point; many fear heavy tweed for its heft and warmth. But we do not similarly condemn our ordinary outerwear, and what is keeper’s tweed other than cloth for wearing outdoors?