Field Survey

From top to bottom, a good start.

Now that Memorial Day (in the US) has passed, any of the largely ignored restrictions regarding seasonal colors and materials are lifted. White, cream, pastels, linen, raw silk, straw—these shouldn’t look out of place for the coming months. This is particularly true of outdoor occasions, where whatever reluctance might remain in combining some of the above is assuaged by the prospect of standing in the grass with a Pimm’s. Nevertheless, the garden party—for our purposes, a social gathering that takes place on or in the vicinity of a lawn—presents additional challenges to those who care about clothing and comfort.

I understand women have a whole genre of shoes specifically designed not to aerate the lawn, from flat sandals to stubby and flanged kitten heels. A different concern lurks for men: moisture. Grass, when green, is wet stuff, even if following several days without rain. A prolonged stay sole-deep in the foliage can rather quickly soak through a shoe. I avoid particularly thin-soled or lightly constructed shoes. A double-soled monkstrap is good here, or, if you must, a rubber sole in the form of white or dirty bucks. One word of caution: lighter colored leathers and suedes, spectators, and loafers with twill vamps are susceptible to grass stains.

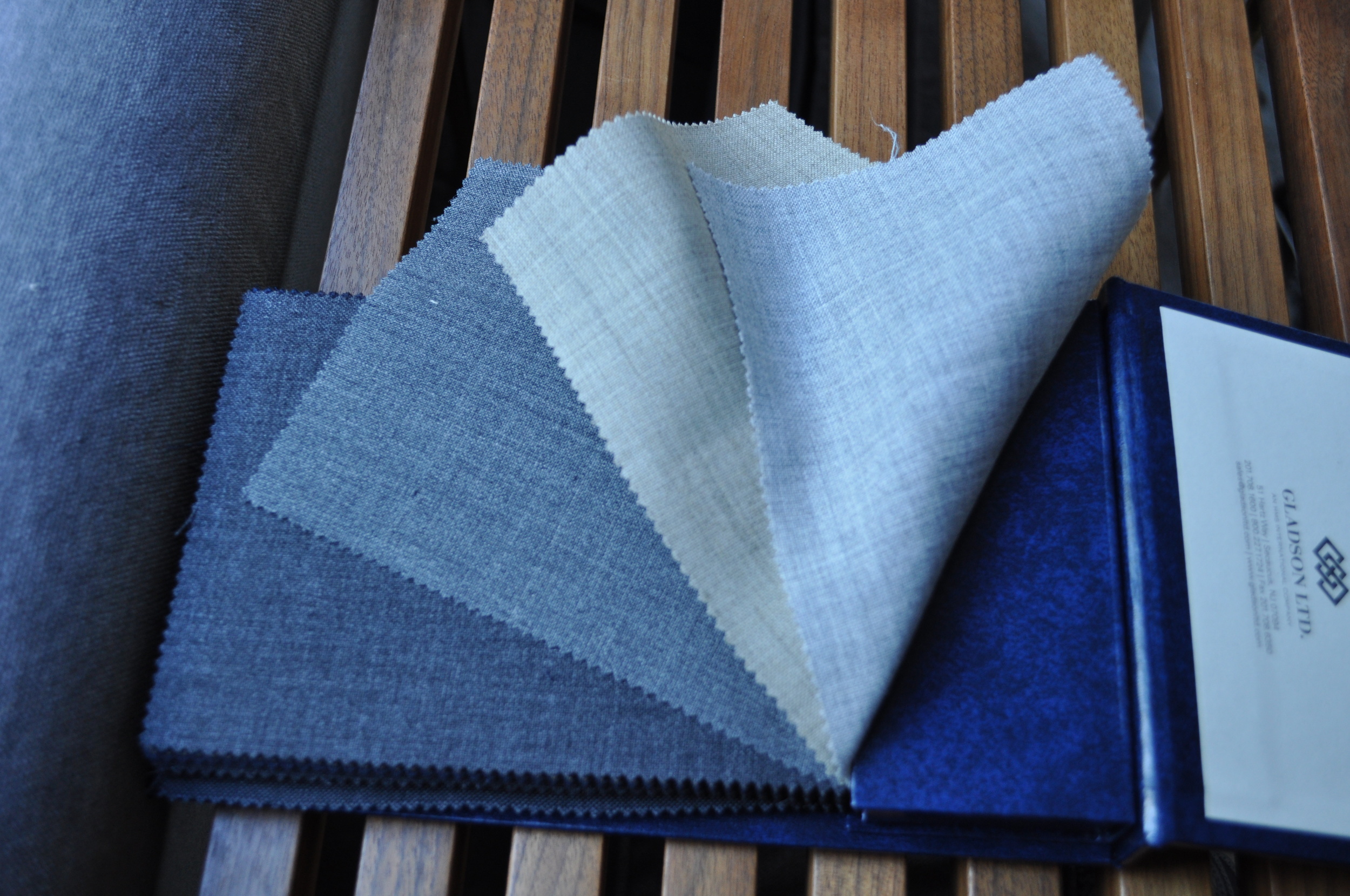

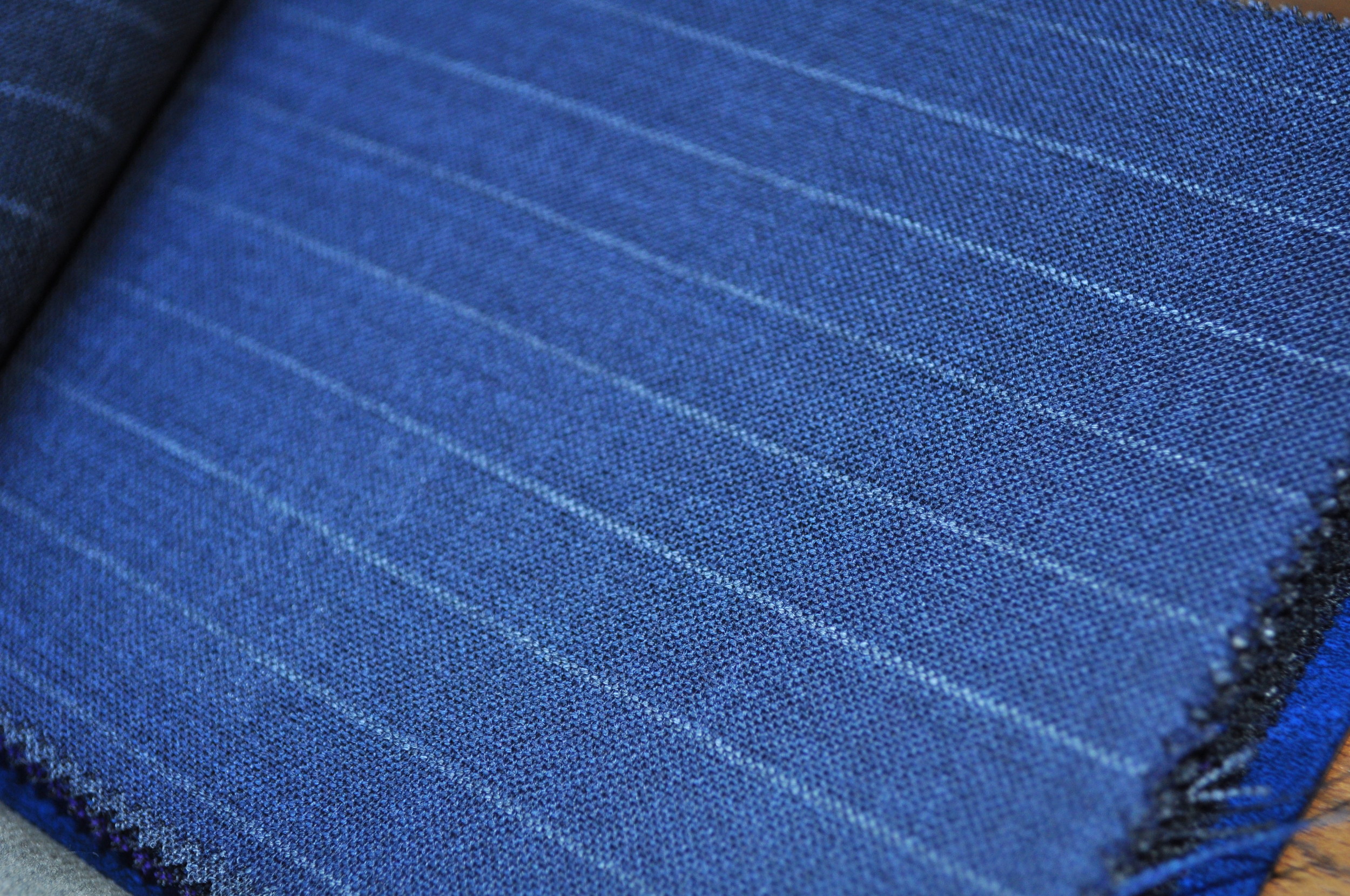

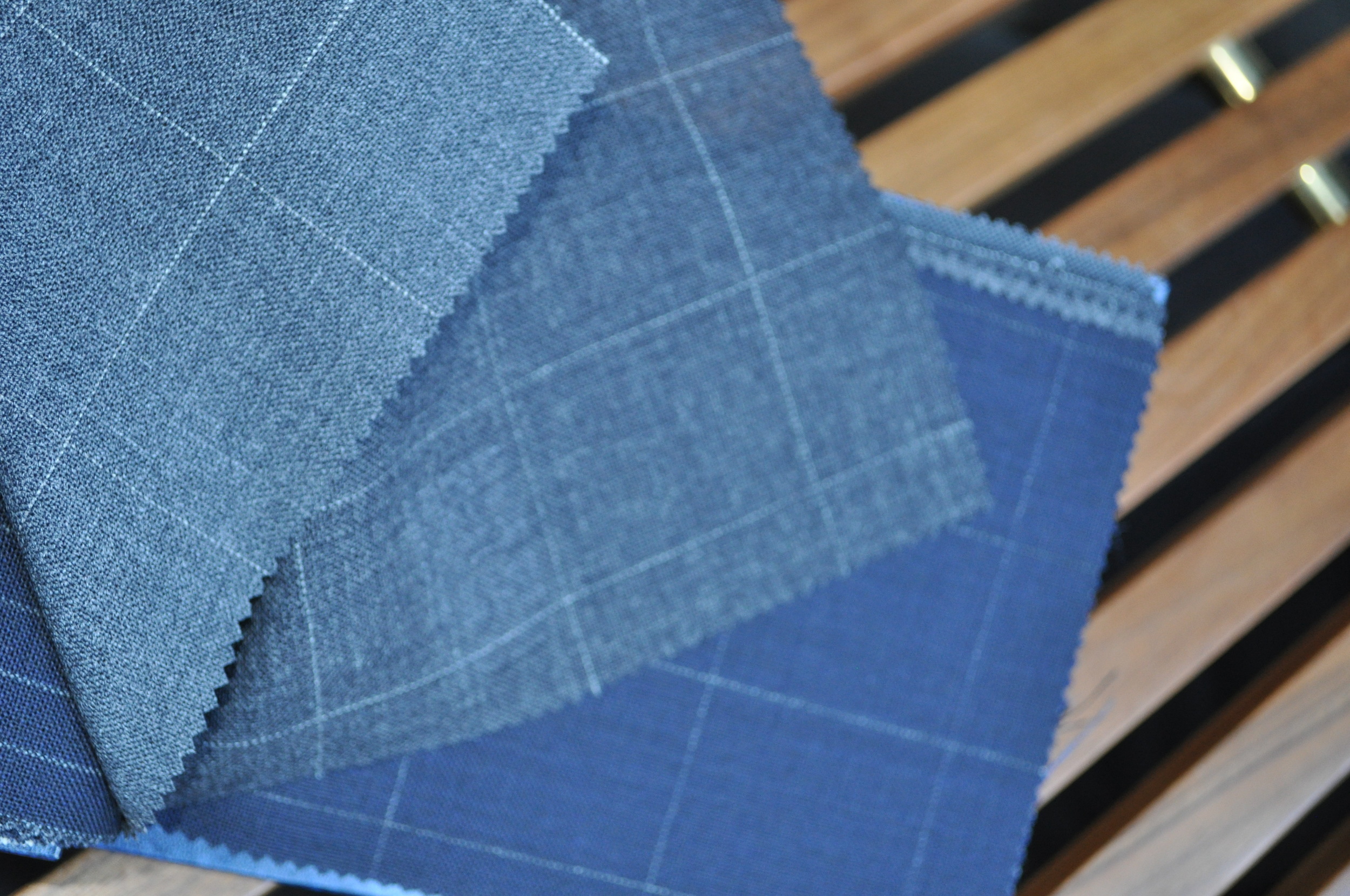

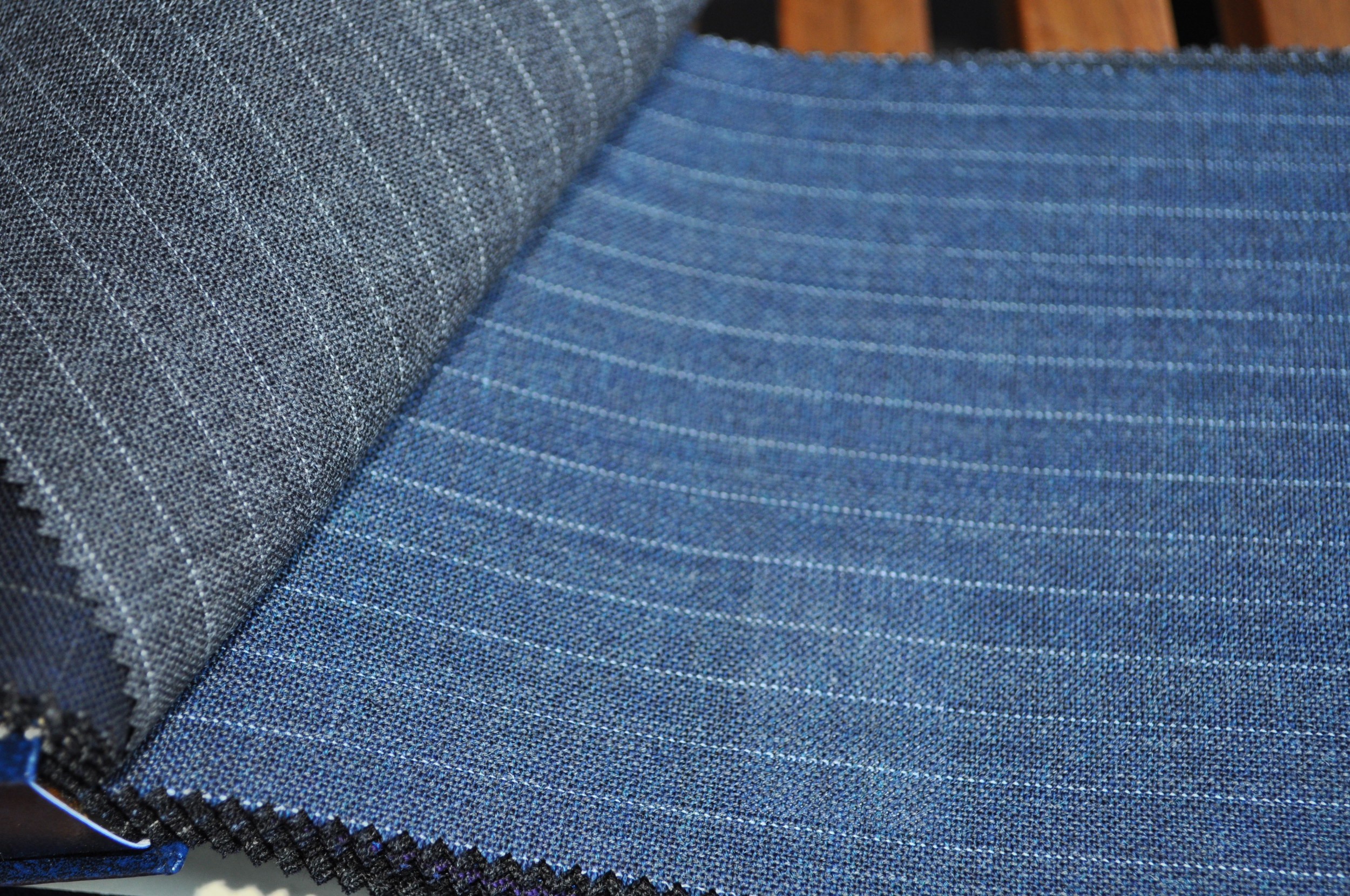

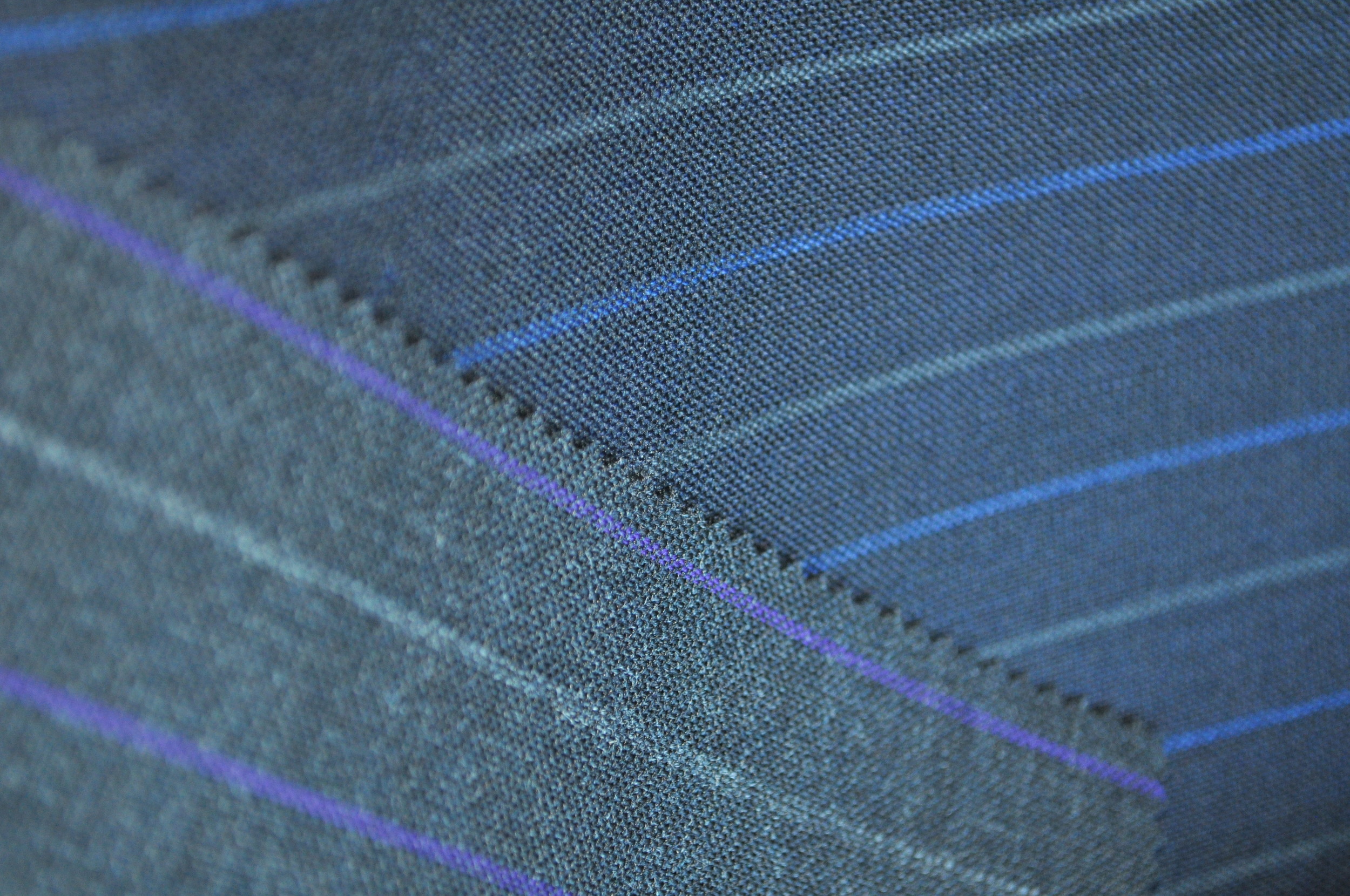

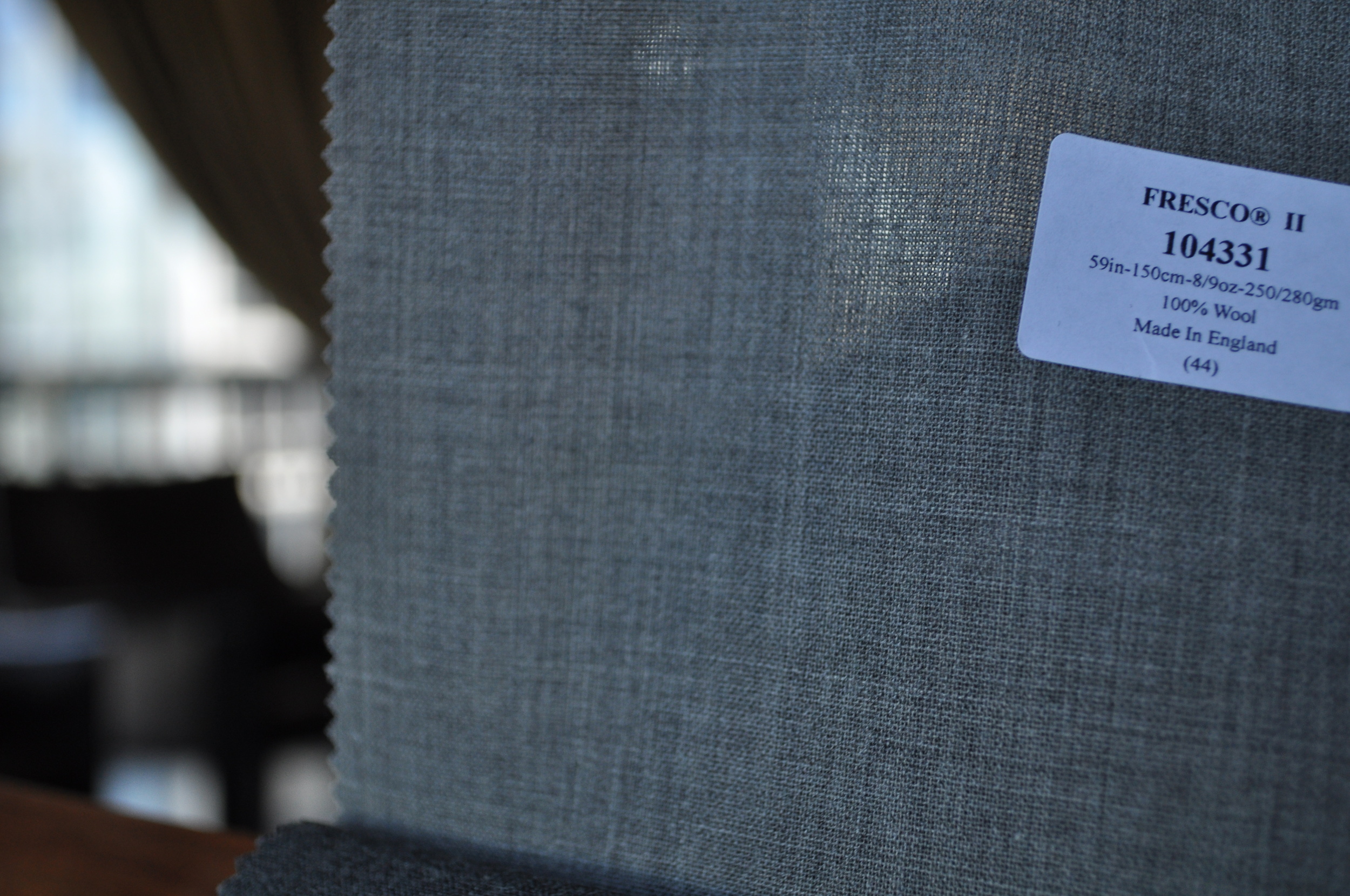

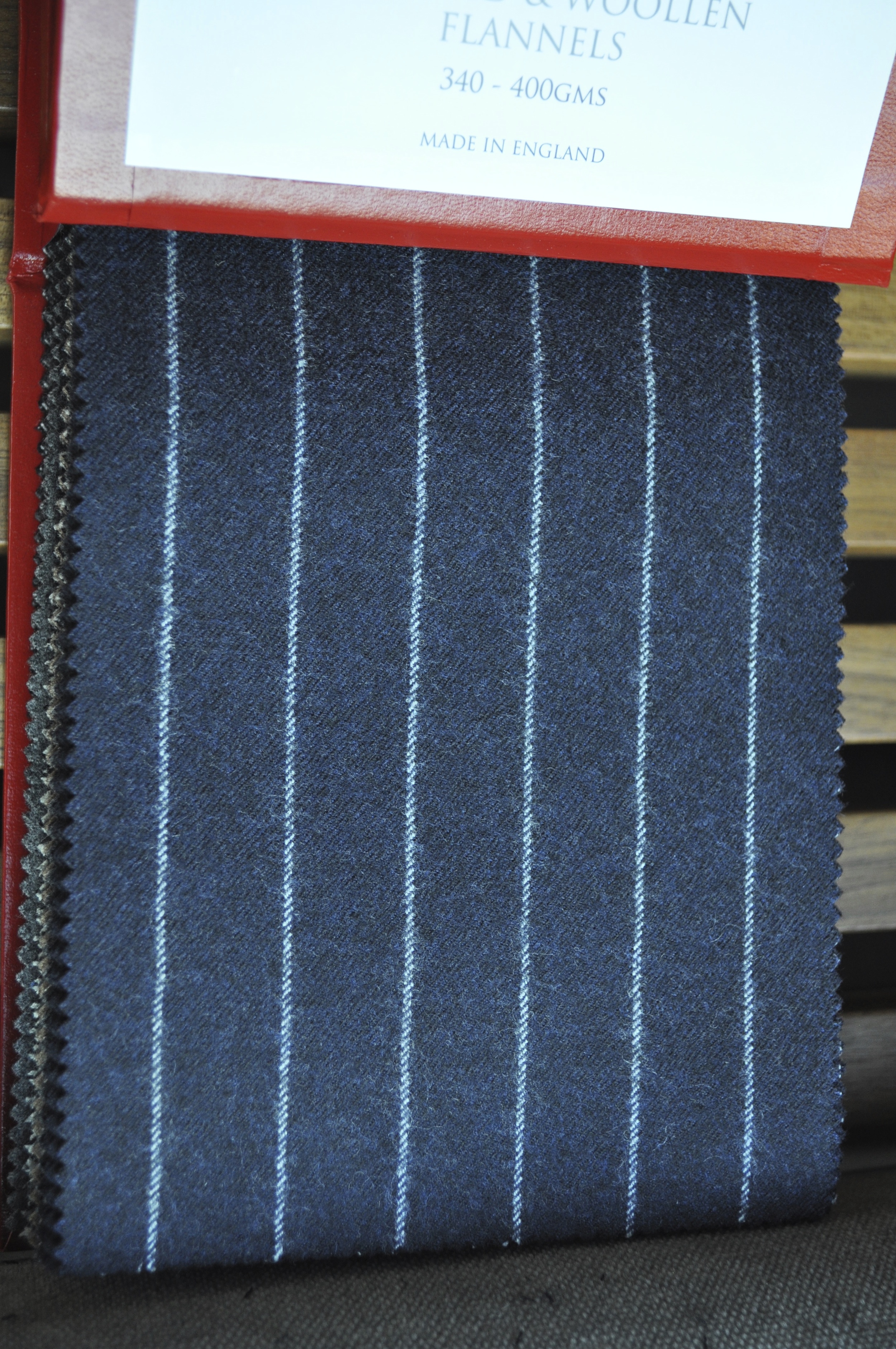

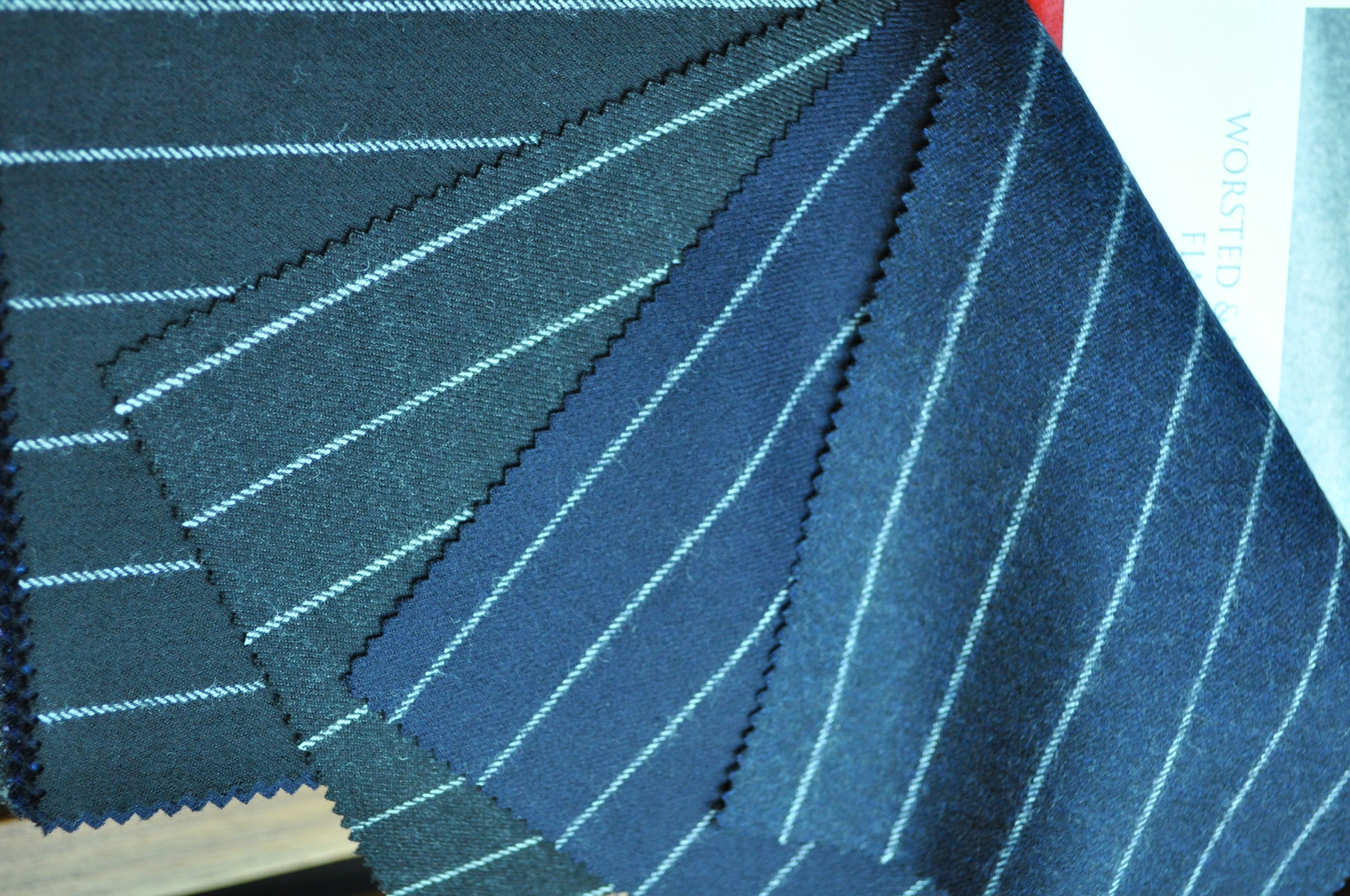

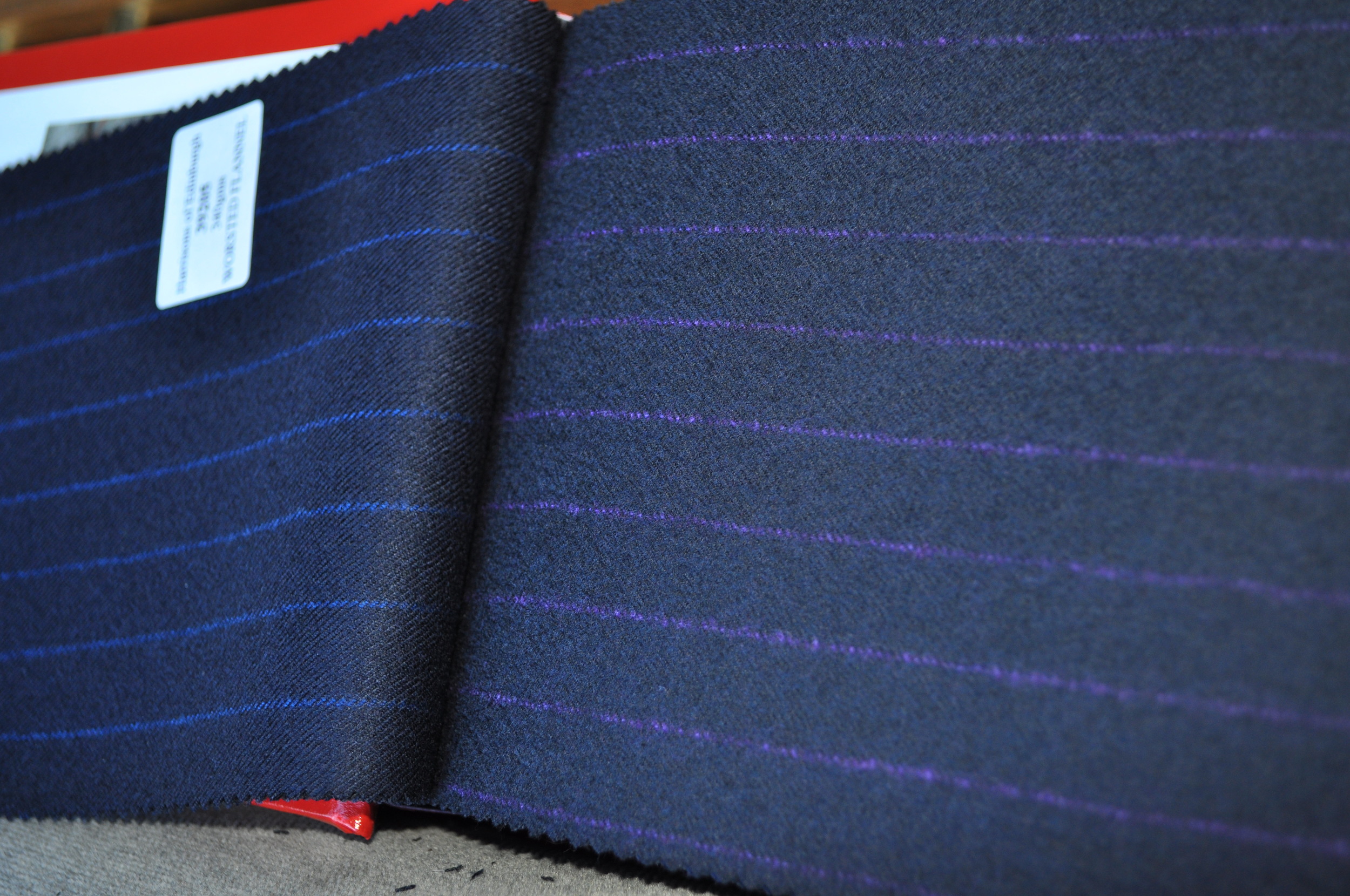

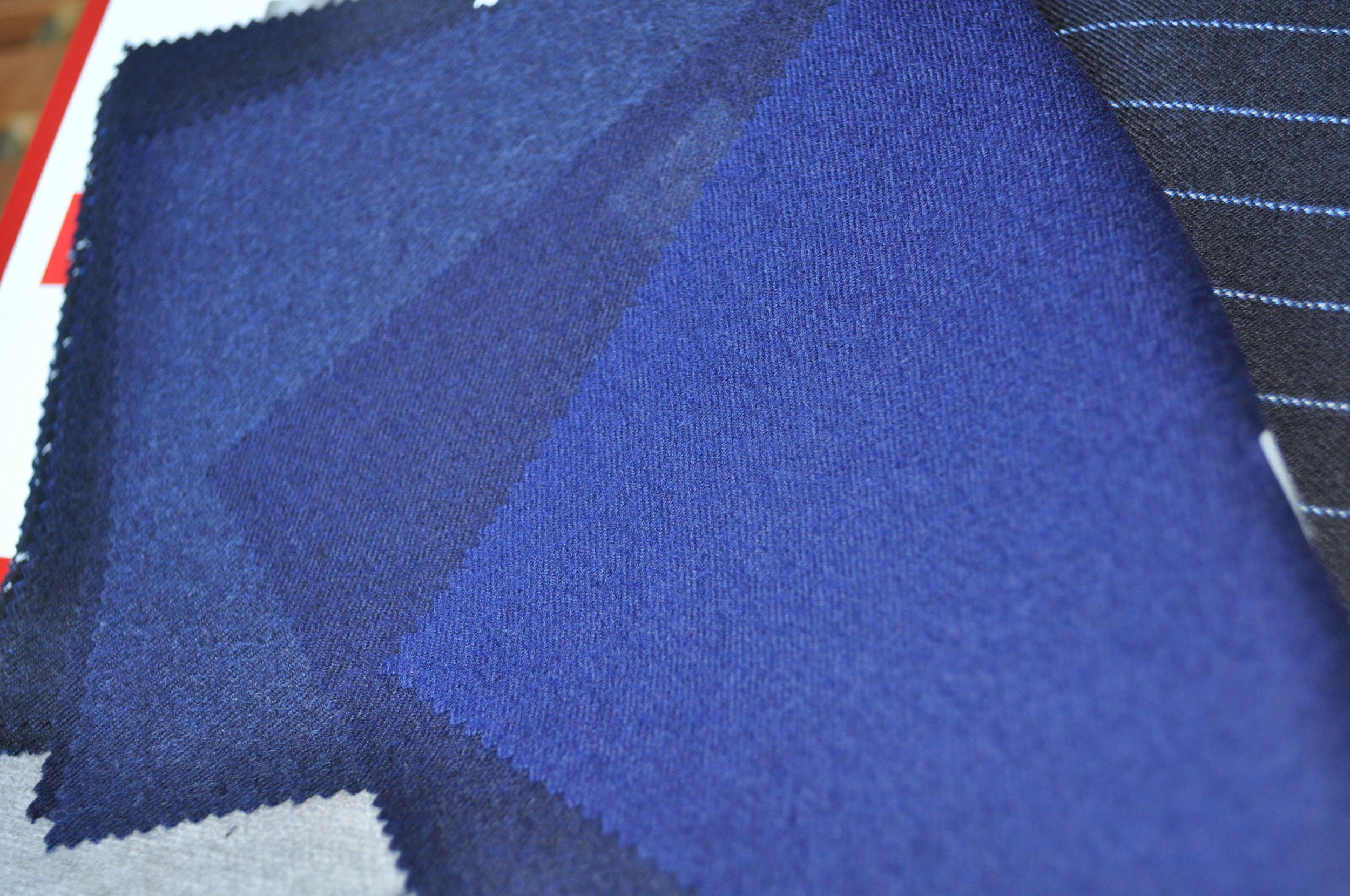

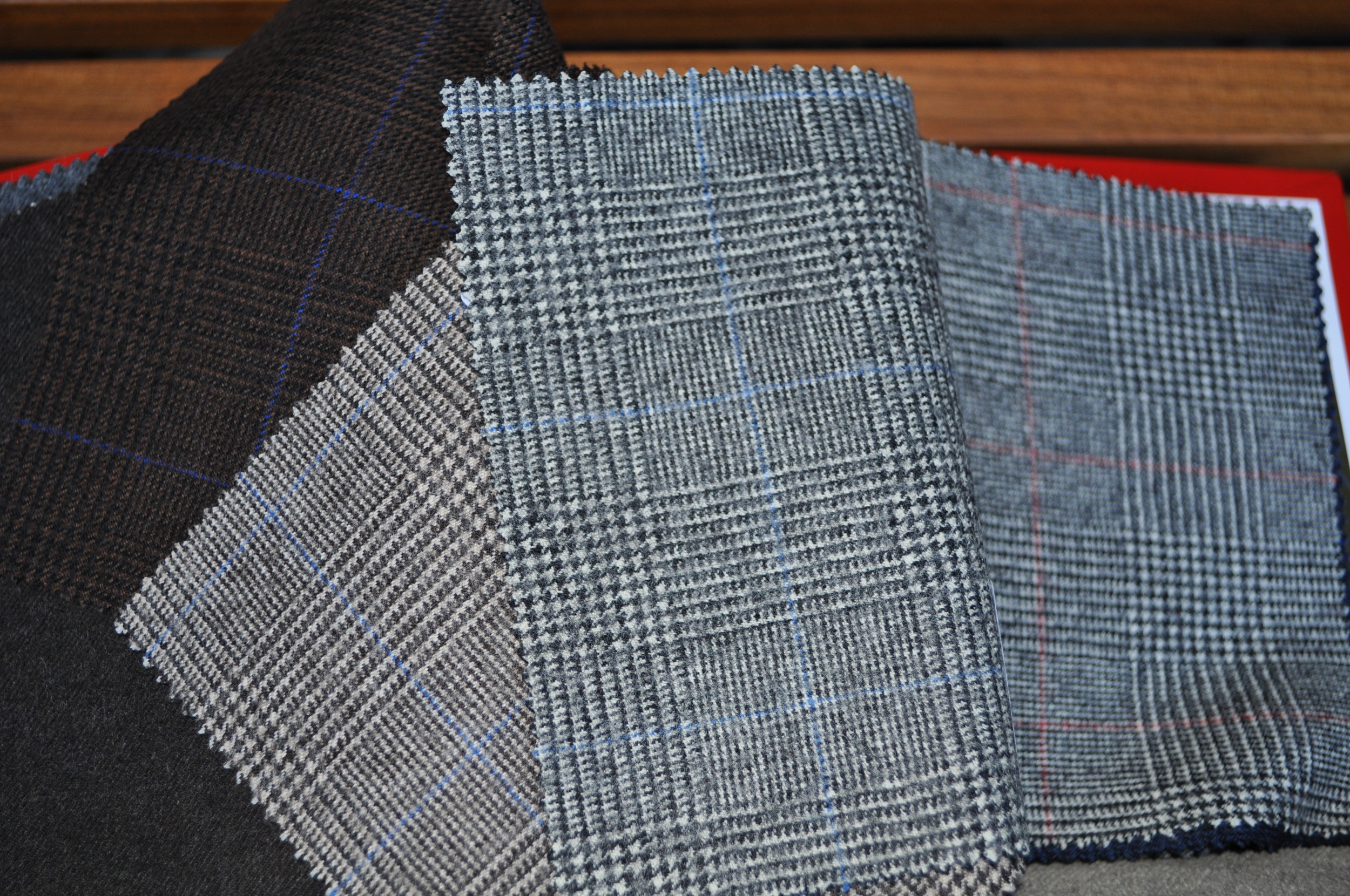

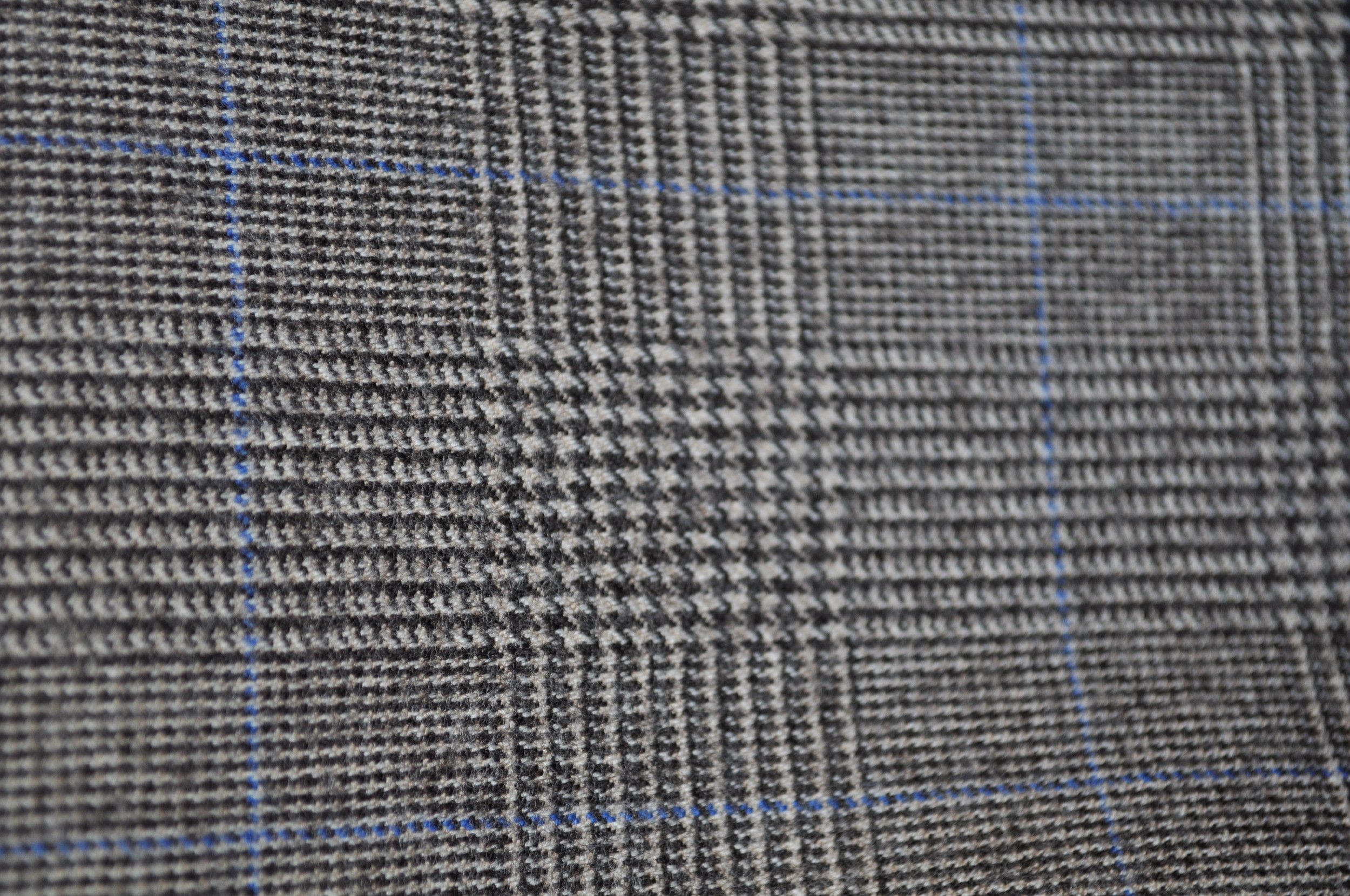

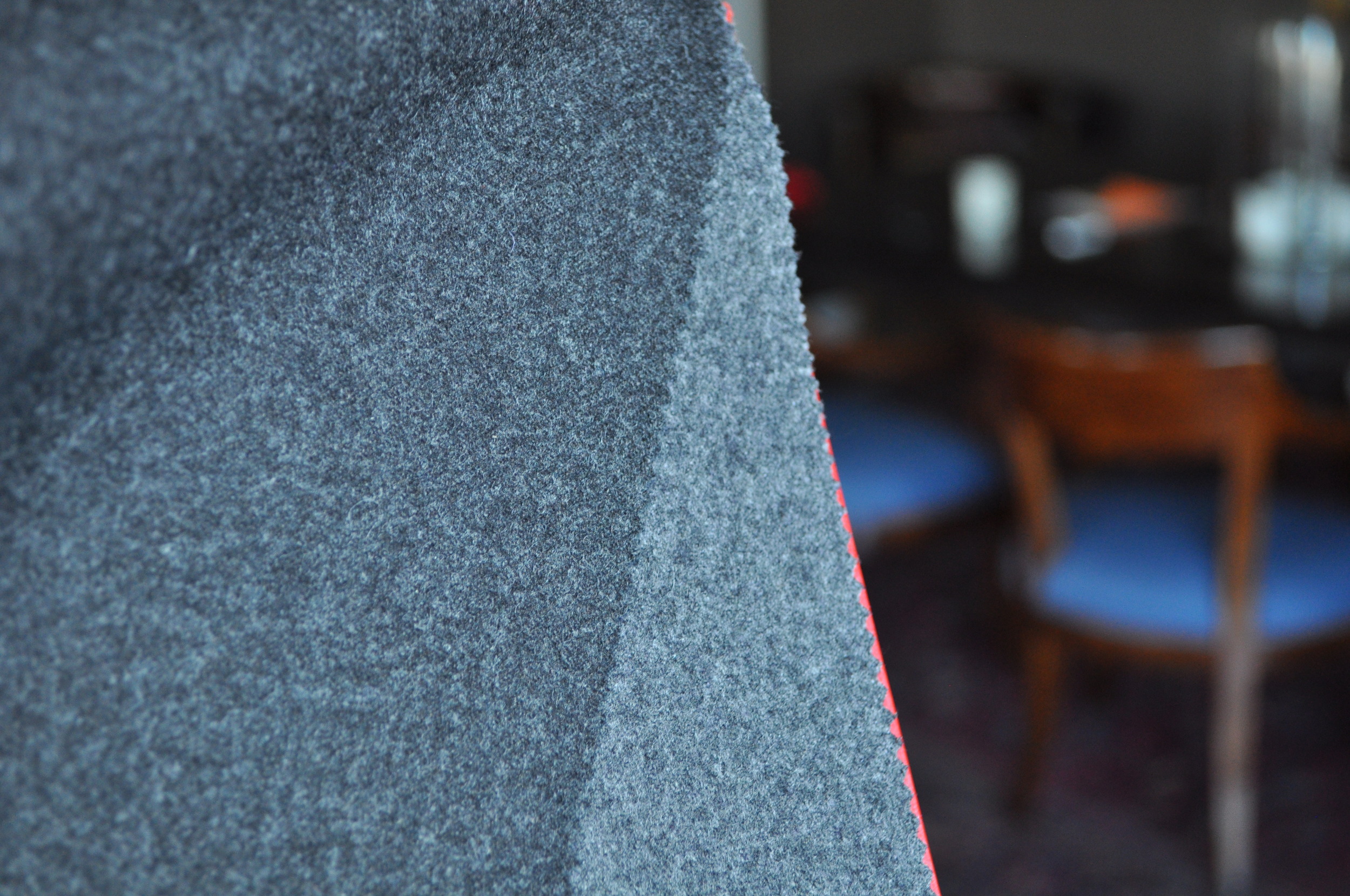

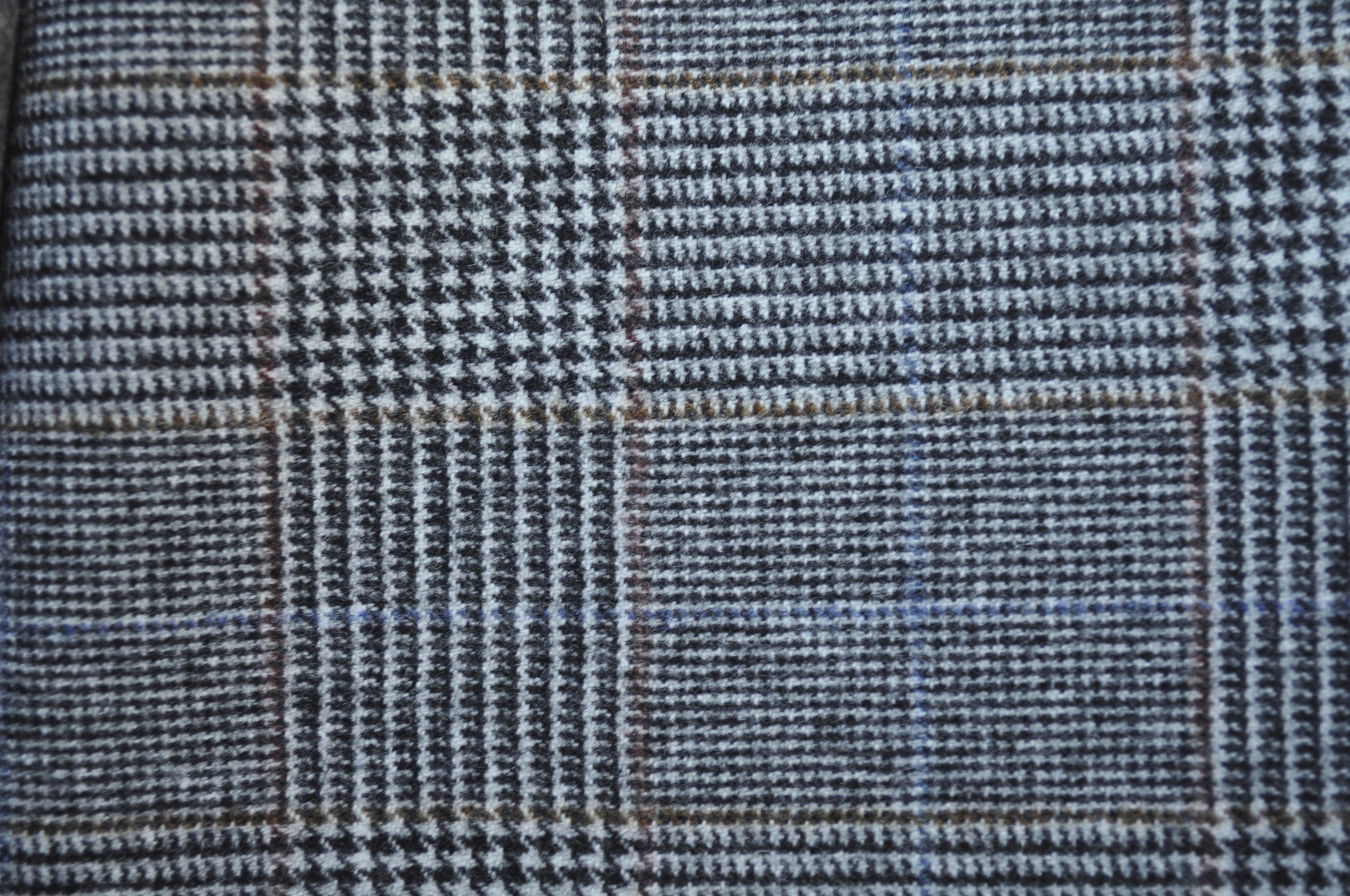

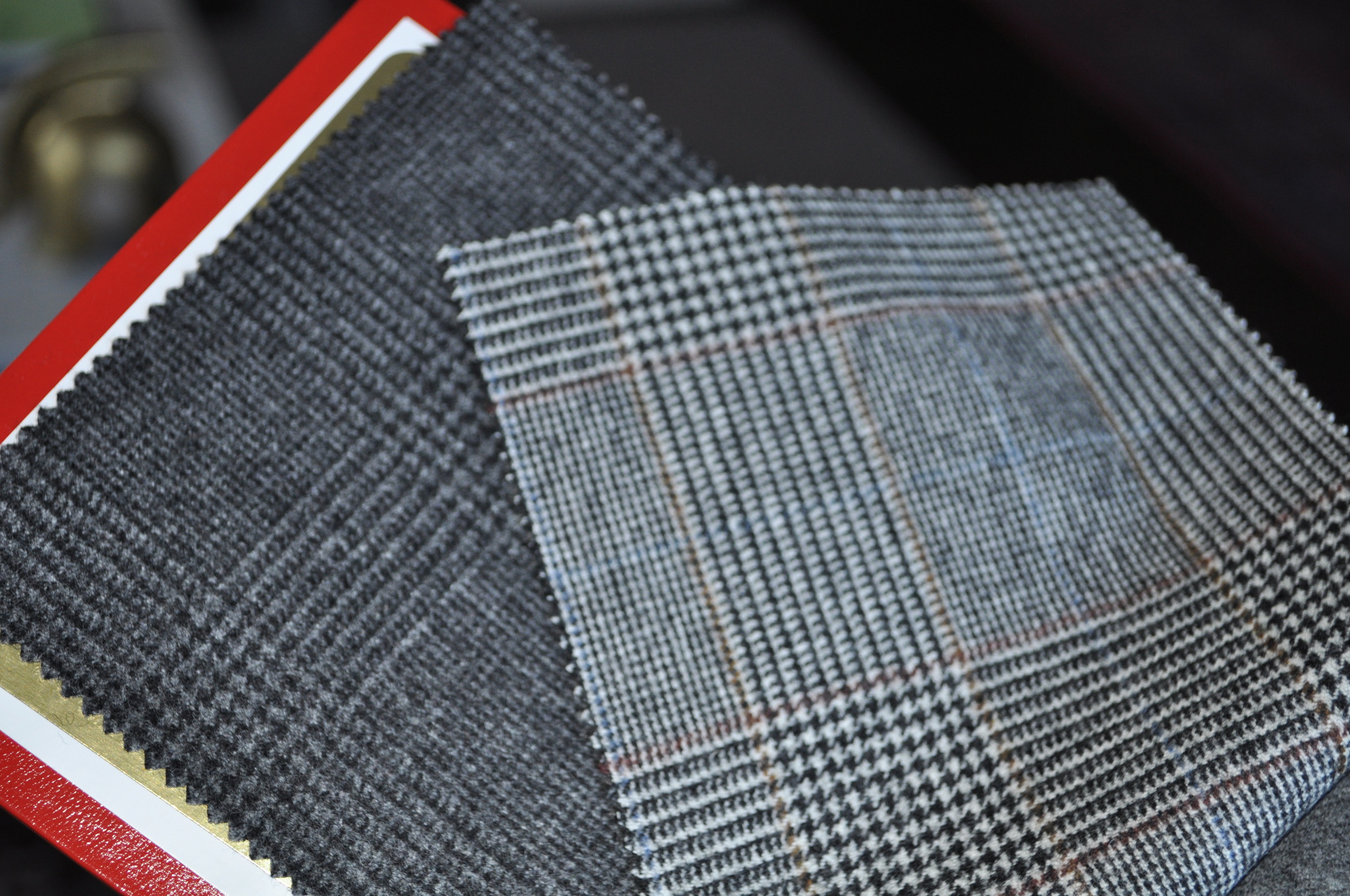

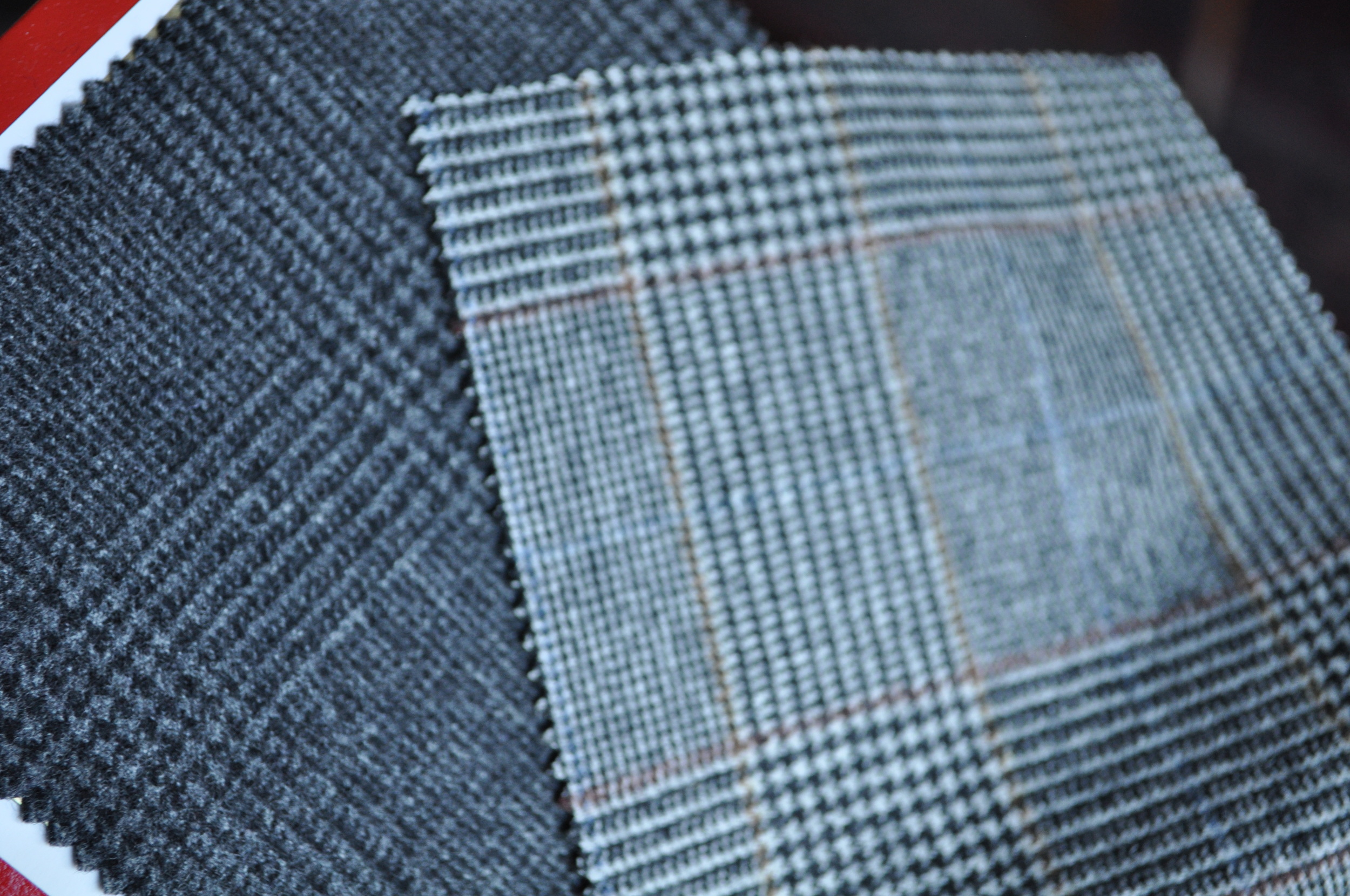

That damp grass creates another problem: ground humidity. I almost melted once at a charity benefit in mid-weight cotton drill trousers even though it was only in the mild mid-seventies. If it is sunny, the relative humidity on the lawn will increase sharply. Instead of cotton, a porous, lightweight wool or linen works better. The former disperses the damp heat, the latter, at the expense of wrinkles, permits evaporation. The most important aspect to a trouser in these conditions is porosity; any tightly woven cloth is going to allow rising humidity in without providing much of an escape. The result is like being stewed from the waist down.

Porosity is when you can see the garden through your trousers.

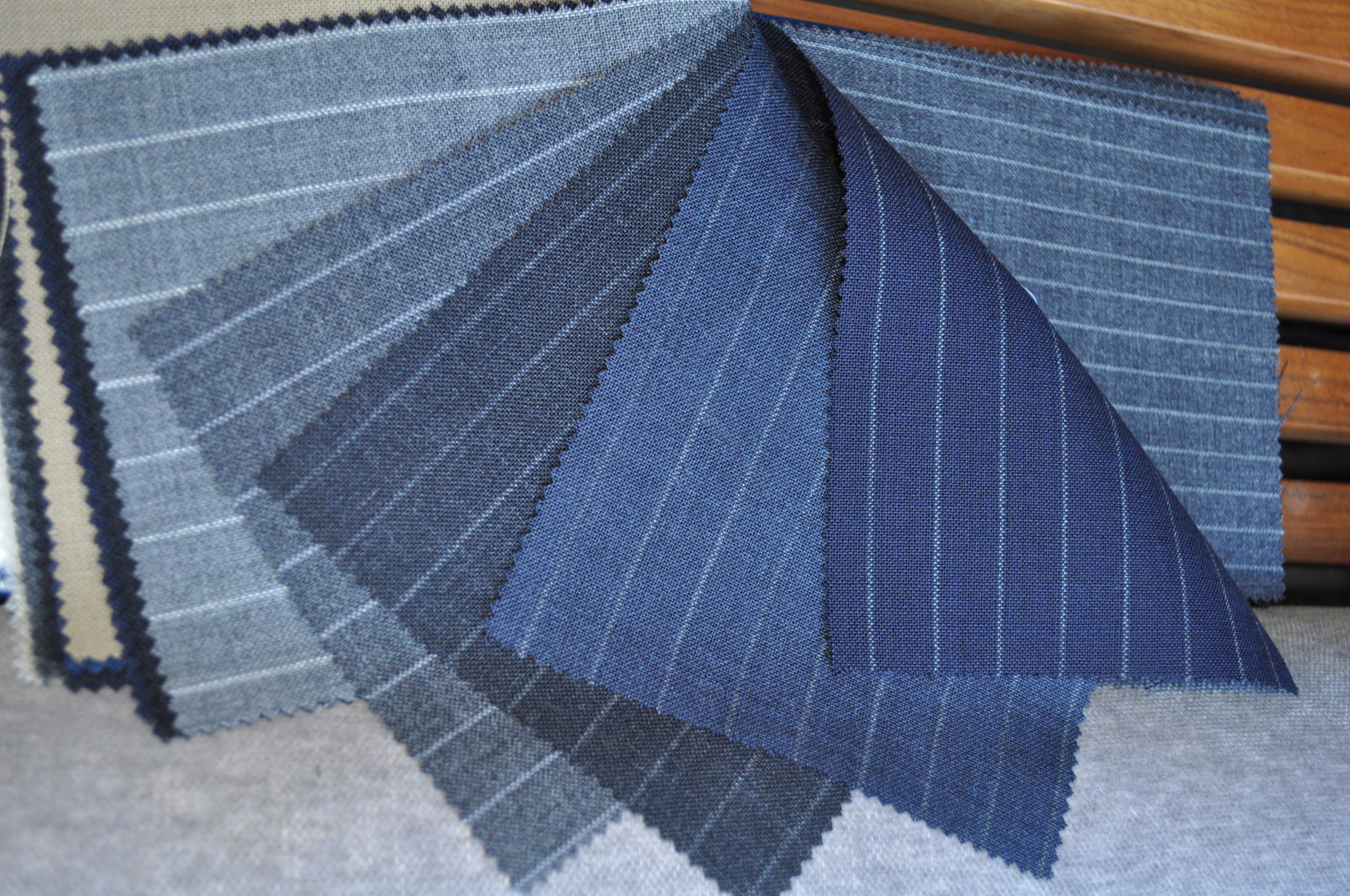

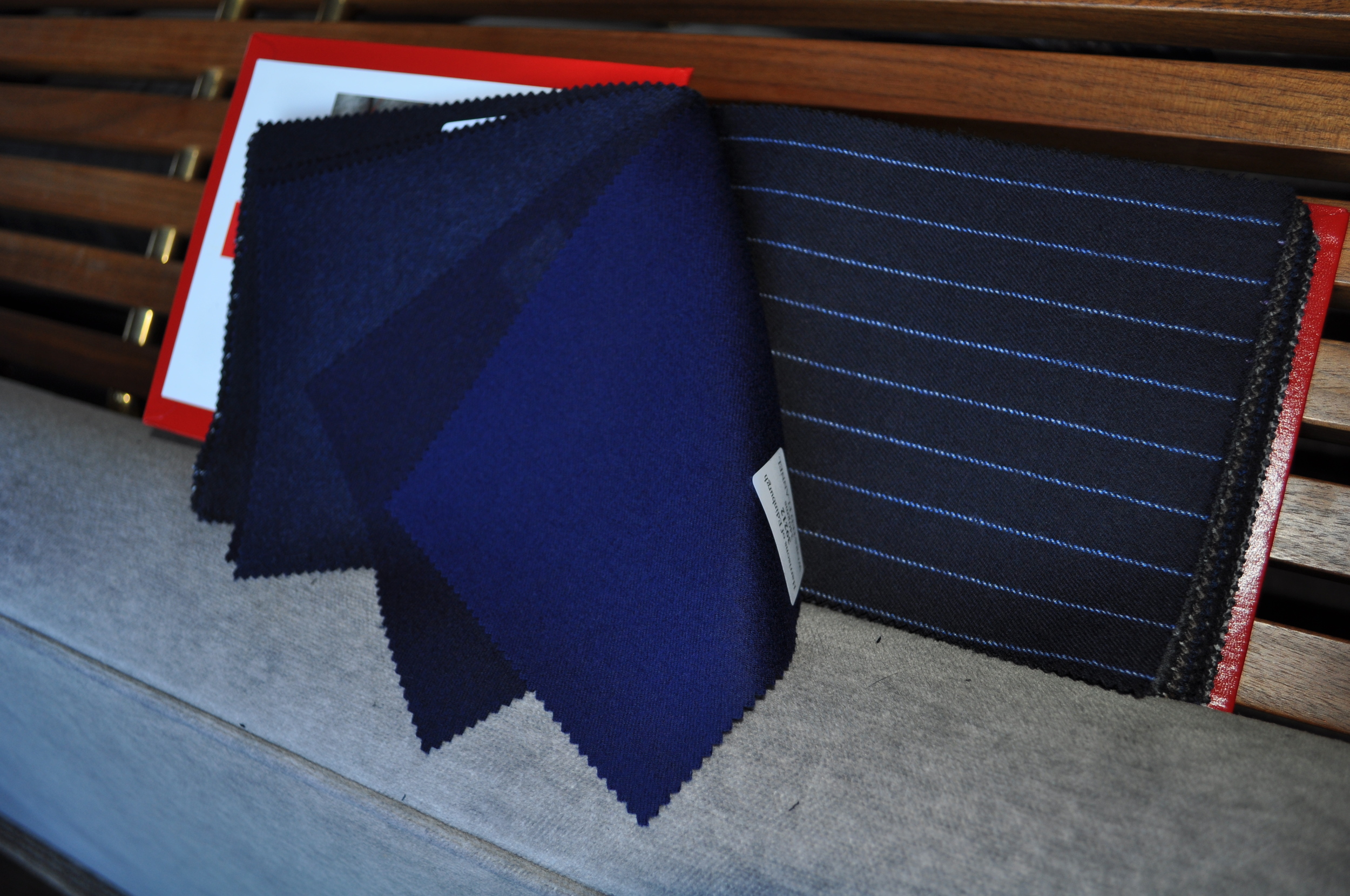

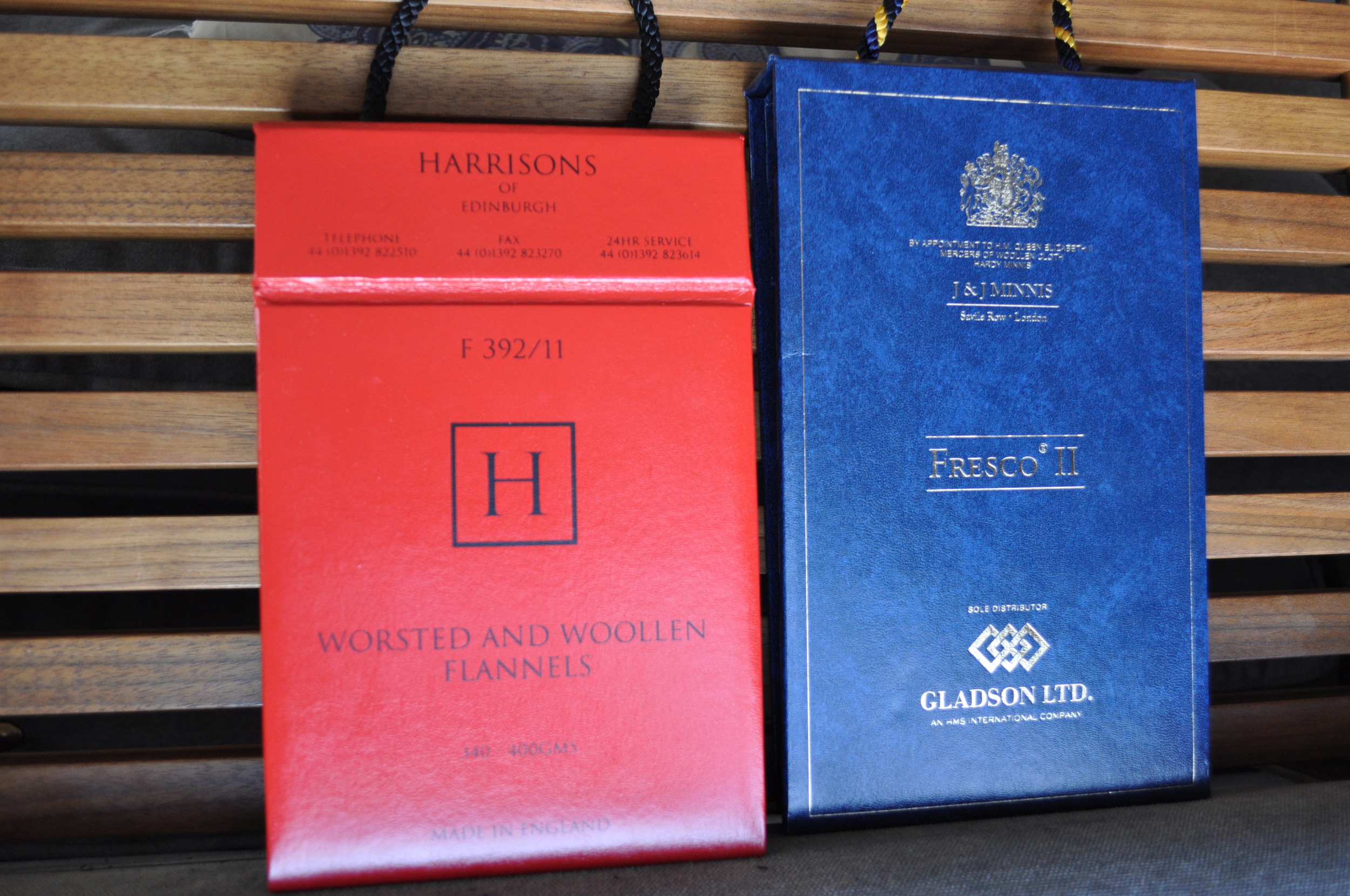

Porosity is important for your upper half as well. A shirt in a cool-wearing open weave is important. Royal oxford is a good compromise between comfort and opacity. Voile is very cool but is fairly sheer—a problem for those with darker chest hair. Your jacket should be made of one of the previously mentioned trouser cloths. I say one of because, depending on the formality of the event, you’ll either be in a suit or odd elements. Lightweight wool, especially something textured like Fresco, goes well with linen and, it could just be my imagination, but odd jacket and trouser combinations just seem cooler-wearing than suits.

Finally, if the sun is truly out, a straw hat is indispensable. This can seem counterintuitive as it is another layer and the inside band might stick to your forehead. But there are far worse symptoms of an exposed melon: a higher body temperature, the need to squint, sunburn. If your head feels hot, simply remove your hat for a few moments and let evaporation do its thing; this will afford an opportunity to display your dexterity in the juggling of cocktail, hat and brow-mopping handkerchief.