Punching Up

The guilty urn, retired along with Madame Bovary, to a shelf where it holds nothing more potent than old corks.

The first Christmas my wife and I spent married we had the idea of starting, from the thinnest winter air, a tradition: we would host a party. Three weeks before the appointed date scores of friends received our invitations, printed, remarkably, on fragrant, cedar veneer. Replies flew back. The house was decorated with swags of laurel, holy, mistletoe, garlands of fir and football-sized pine-cones. I knew a cheese monger at the time, and he organized for me a quarter wheel of Gruyere, a Stilton, an imposing hunk of Parmigiano-Reggiano and a Tête de Moine, the pungent Swiss cheese that, when shaved on a special device, resembles a tonsured monks head. I displayed them on a pane of tempered glass the size of a porch door. A friend in the wine business made some modest selections, and a DJ we knew created a tasteful playlist.

Despite the effort, we felt something missing the day before the party. And then it struck me: Punch! Nothing, I imagined, filled the holiday hollow with genuine spirit—spritzed the chilly scrooge with gemütlich—quite like a shimmering pool of communal drink. I pawed at my small collection of bar-tending books; the options seemed elaborate, or too obscure and all of them rather too sweet. I eventually settled upon an idea suggested in a mercurial addendum: macerating pineapple in spirit—gin, in this case—to be syphoned off and used to mix cocktails with seltzer or tonic. This was ideal, as I had a large urn that would prettily display the pineapple, and the spigot at the base would make dispensing the drams a cinch. I imagined myself a benevolent friar, administering the elixir with a wink and a nod, holding merry court over the glistening and pungent banquet. And so, in addition to four coarsely chopped pineapples, in went three liters of gin.

It was a hit, although an hour into the party I noticed my guests drinking full glasses of the stuff without much in the way of a mixer. I was surprised to see a particularly close friend tapping the liquid dregs with the slurred exclamation, the punch runneth dry! It becomes fuzzy about the edges from this point forward, but I recall several otherwise restrained guests fighting over the gin-sodden hunks of pineapple, each a jigger worth of spirit. One fellow fell asleep in the stilton. The following morning I awoke in my robe on our deck, rather chilly. The uncovered cheese beaded sweat, as did my brow as I surveyed the carnage. The tasteful playlist dumbly played to an audience of upturned glasses, walnuts shells and wilting holly. I’ve tried since to forget the event, but many dear friends still refer to the pineapple incident with some mixture of humor and nausea.

There are at least half a dozen lessons in this anecdote, but one in particular has stayed with me. Traditions cannot be started anymore than can solar eclipses. They emerge, instead, already equipped with debated meaning and foggy purpose. Our intentions might have been innocent, but we nevertheless had been reckless with definitions. Like a tradition, punch is a fixed entity that resists encroachment at the risk of biting back. Don’t misunderstand me: the ingredients and preparations might vary considerably within the genre, but the premise is always the same: wine, fortified wine, a dash of spirit, fruit and ice. The careful reader will notice vast quantities of gin and tropical fruit play no role whatsoever. There is good reason; punch is a social mixture with just enough, well, punch.

Claret Cup

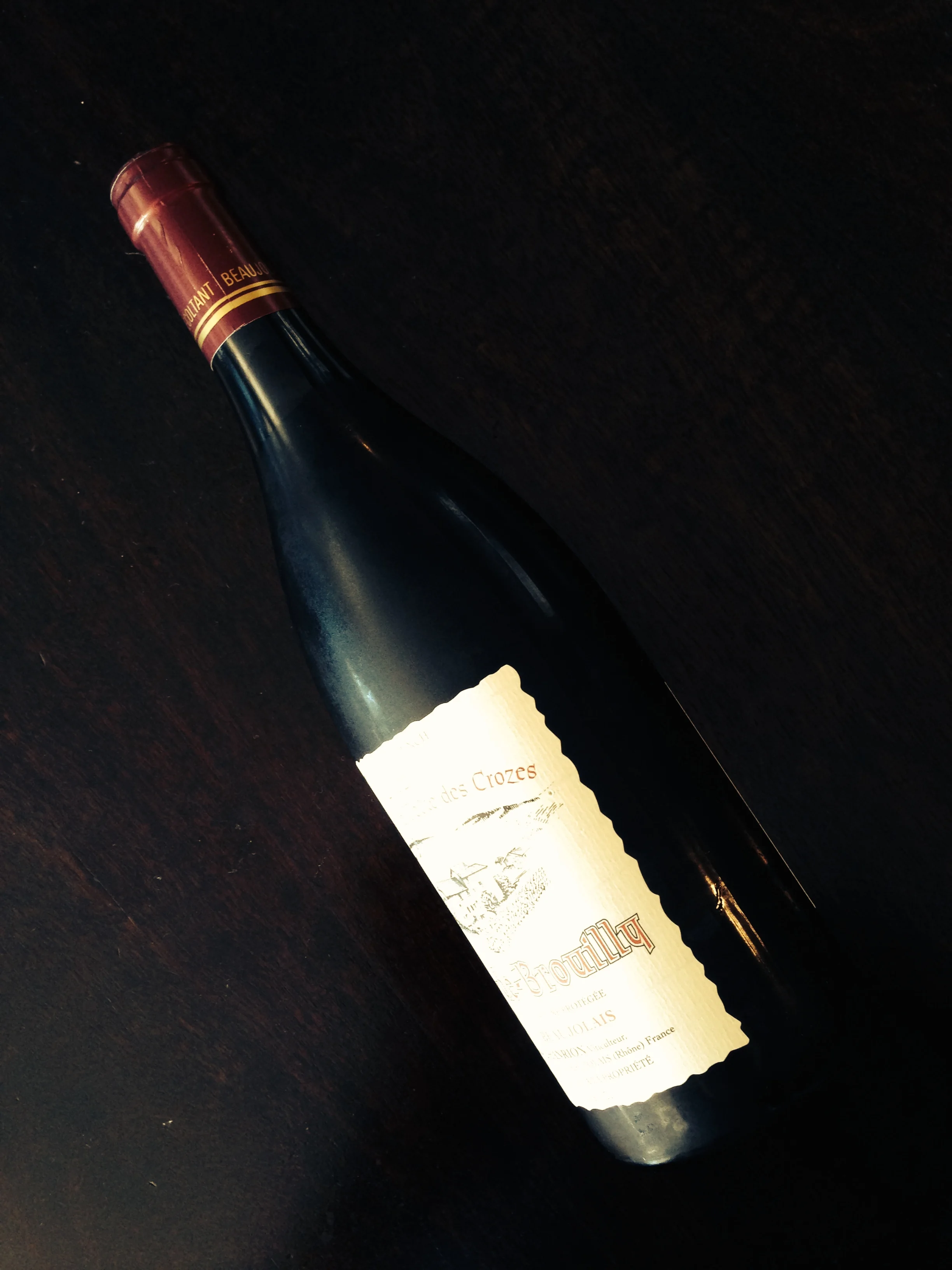

One bottle of mediocre Bordeaux

One cup of Amontillado Sherry

Two jiggers, Grand Marnier

One cup of fine sugar

Two cups seltzer

Orange rind

Stir all ingredients gently in a large stainless bowl. Let sit for thirty minutes, covered in refrigerator. Add one very large block of clear ice. Serve in tea cups with a ladle.